On 24 November 2019 I was privileged to attend a wonderful full-stage performance of Parsifal in Nanjing, the capital of Jiangsu Province, China. Performed by St Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theatre, the production and performers included the following cast of main musicians.

Parsifal: Mikhail Vekua

Kundry: Yulia Matochkina

Amfortas: Vadim Kravets

Gurnemanz: Yuri Vorobiev

Klingsor: Mikhail Petrenko

Mariinsky Orchestra, conducted by Valery Gergiev

This was a really extraordinary experience from several points of view. Firstly, it is the first time Wagner’s last work has been performed in Nanjing. This may be a major Chinese city, but Wagner is still quite rare in China, and Parsifal is full of content that might seem inimical to the political atmosphere there.

Secondly, although the Mariinsky Company gave the same work in Beijing two days later, it was a concert performance only, whereas Nanjing was able to enjoy a full-stage production. The reason for this is that it was the Jiangsu Provincial Government that had made the greatest efforts to organize and sponsor a full Mariinsky Festival.

Thirdly, the production and performers were entirely Russian. During the intervals I was able to observe the orchestra, which had no Chinese players. The singers from Parsifal to the second squire were all Russians. It must have cost a fair amount to transport and insure so many people and their instruments. There is of course no earthly reason why Russians should not excel in Wagner, and Parsifal had its Russian premiere as early as January 1914. However, this work is still not one to be particularly associated with Russia. All the singing was in German.

The present performance of Parsifal is part of the 2019 Mariinsky Festival, which saw Chief Artistic Director Valery Gergiev and the Mariinsky Orchestra of St Petersburg undertaking a tour of China, focused on Nanjing and performing a series of concerts, opera and ballet. In Nanjing, ballets include Firebird by Stravinsky and Sheherazade by Rimsky-Korsakov, while the concerts include the Shostakovich 5th, Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony, Debussy’s “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun”, and other works that loom in the great works of the repertoire. In Beijing, there were three concerts, including a concert performance of Parsifal and concerts focused on the music of Rimsky-Korsakov, including Sheherazade, and Berlioz.

It is obvious that the Jiangsu government has invested a good deal in this festival: apart from the wide range of performances, it subsidises all tickets. The Bank of Jiangsu was also a major sponsor. It seems to me to represent something of a cultural coup for China’s relations with Russia. The strong relations between Putin and Xi Jinping have been clear for some time and much commentary has focused on the ramifications for Sino-Russian relations. Less attention has been given to the cultural side of things. And I find it very interesting indeed that, though the Russian performers are given focus, there was comparatively little attempt to prioritize Russian music. A festival of this sort could as easily have performed Boris Godunov as Parsifal.

Overall, the Parsifal performance was simply marvellous. Musically, of course, it cannot compete with Bayreuth or a range of other places, but all the singers were good and Gergiev managed to get a splendid and intense sound out of the orchestra. Also, I like the traditional and lavish production, which gives the Grail Scenes the grandeur that Wagner intended.

I had never heard of any of the singers, and among the performers only Gergiev’s name was familiar. As Parsifal, Mikhail Vekua was good vocally, but not a very good actor. He sang “Amfortas, Die Wunde” in Act II very well, with ringing high notes. But he got some of his words wrong, especially in Act III.

Yulia Matochkina as Kundry acted more convincingly than Vekua, and sang with a powerful, definitely mezzo voice. In the place in Act II where she tells Parsifal that in a previous life she had mocked Christ on the Cross, she got the high B in “lachte” (“laughed”), by sweeping up to it, rather than attacking it head-on, but it was effective and powerful. She followed Wagner’s intentions by sinking lifeless but redeemed at the end. I thought it a slight pity that just before “Amfortas, Die Wunde”, there was no attempt at a seduction scene, and Kundry did not approach Parsifal when she talked about “love’s first kiss”. He approached her briefly and tried to kiss her, but then very quickly rejected her.

Kundry takes a bow at the end of Parsifal. To her right is Klingsor, to her left Amfortas, flower maidens and others.

The Amfortas (Vadim Kravets) was just excellent. His voice is powerful and true, and he sang with the feeling and intensity the part demands, as well as being a good actor. The Gurnemanz (Yuri Vorobiev) definitely looked the part, tall and strong, definitely designed to resemble the traditional Russian monk. In terms of singing, he was very good but occasionally slightly out of time with the orchestra. The Klingsor (Mikhail Petrenko) was somewhat weaker vocally but acted very well. Apart from his main scene at the beginning of Act II he could be seen occasionally slinking across the back of the stage investigating how Kundry was faring in her attempt to seduce Parsifal, equivalent to his own wish to bring down the “innocent fool”.

As one would expect from Gergiev, the orchestra was excellent. The woodwind was just superb, especially the first oboe, which plays in several very significant passages, such as the opening of the Good Friday music. One thing I do criticize is that the trumpet in the opening minutes of the Prelude was not completely in time with the rest of the orchestra. However, when the same music returns during the Grail Scene, the trumpeter was absolutely wonderful and the musical effect overpowering. The transformation scene in Act III was suitably loud and grave.

Turning to mise-en-scène, the best way to characterize is that production and costumes were traditional, and gave the medieval flavour that Wagner intended.

Gurnemanz and the knights were dressed like medieval people. The flower maidens in Act II all had clothes different from each other but there was a rather Russian or Central Asian feel to their scene. Kundry was dressed magnificently and beautifully in Act II, but in rags for most of Act III.

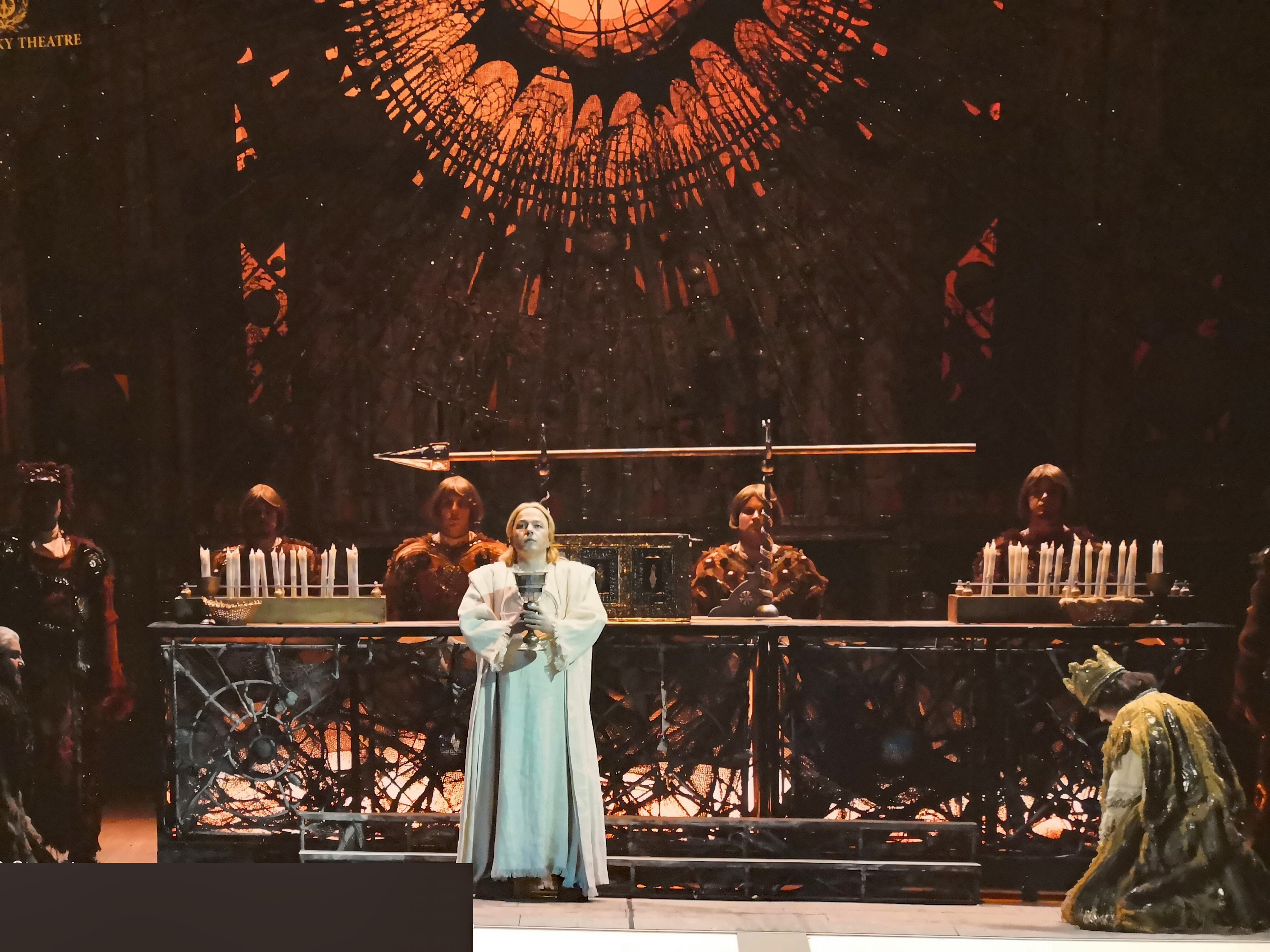

The Grail scenes were very majestic and lavish, with a tabernacle on an altar at the back of the stage, from which the Grail was taken. At the end of Act II, Parsifal did make the sign of the cross when he destroys the magic garden, which is probably what Wagner intended when he gives Parsifal the word “mit diesem Zeichen bann’ ich deinen Zauber” (“with this sign I destroy your magic powers”). I found this striking, because, in stark contrast to many productions, it demonstrated this one as showing no attempt to diminish the Christian symbolism of the opera.

The final scene, with Parsifal holding the Grail and Amfortas kneeling beside him.

A couple of things were disappointing about the production. One was that Klingsor’s scene seemed to have a half-built modern city, with half-built flats at either side and lights at the background. It was the only part that departed from the medieval atmosphere of the opera. The other was that in the scene in Act III where Titurel’s coffin should be opened, as shown by the extremely dramatic music in the orchestra and chorus, everybody was motionless, and the coffin remained closed throughout.

But overall, I found the production thrilling. It really gave the atmosphere of the music and story of the opera in a way which was totally lacking both in the minimalist production in February 2019 in Melbourne and in the ultra-modern and overly politicized Bayreuth productions. One really got a sense of Amfortas’s anguish and Kundry’s contradictory character in the three acts, of fulfilled hope and redemption amid despair.

There were a few foreigners in the audience, but the overwhelming majority were Chinese. What did they think of it? Since this performance was so unusual an event in China, this question is worth asking.

The lower parts of the theatre were entirely full, as far as I could see. There were quite a few children, including at least one class brought by a teacher. During the interval after Act I, I asked one of the girls what she thought of it, and she and her teacher both expressed approval despite the fact that the first act is so long. I met by accident with a media personality who thought it was wonderful but also (quite reasonably) impressed on me the significance of Kunqu, a classical form of Chinese theatre, which comes from this area. The young man sitting next to me was wide awake the whole time and told me he had been to several concerts of the Mariinsky Festival and loved the ballet just as much as the opera. He had never heard Parsifal before, but was deeply impressed with it. Several others commented to me how splendid they thought the whole performance was and how much they liked it.

The interior of the lower part of the Opera House.

One point on the negative side was that the audience started applauding when the curtain began closing, not when the music stopped. At the end of Acts I and III, which feature long drawn-out chords, there was a gap between when the applause started and the music stopped that I found disconcerting. I think the Chinese in general are not familiar with a work like Parsifal but definitely like it and want to show enthusiasm. A cynic might say they are just glad that this long work is over. However, applause before the end is not confined to Nanjing and it common in New York and other places too. Applause was enthusiastic for all three acts, including the first for which the tradition is to have no applause at all due to the solemn content; and there was a standing ovation at the end.

There seems to be something of a push towards the Western classics among a certain clientele in China. I find it interesting, and even a bit surprising, that the Jiangsu and other governments are pushing an opera like Parsifal. No doubt it is mainly a function of the excellent state of Sino-Russian relations. But nobody seems to have heard of the charges of racism and patriarchy sometimes levelled against this opera, or be concerned about it if they have.

A few other peripheral points are worth making. The performance stated at 4:15 (fifteen minutes late), and there were two intervals, each of half an hour. During the first interval, each person was given, free, a small packet of a triple-barrelled sandwich, a small pot of yoghurt and a plastic bottle of water. There are places to buy food near the theatre, including a Starbuck’s where sandwiches and cakes are available, but the intervals were not long enough to go there.

There were subtitles of the text in Chinese only on both sides of the stage. In Western-style operas at the National Centre for Performing Arts in Beijing, the common practice is subtitles both in English and Chinese.

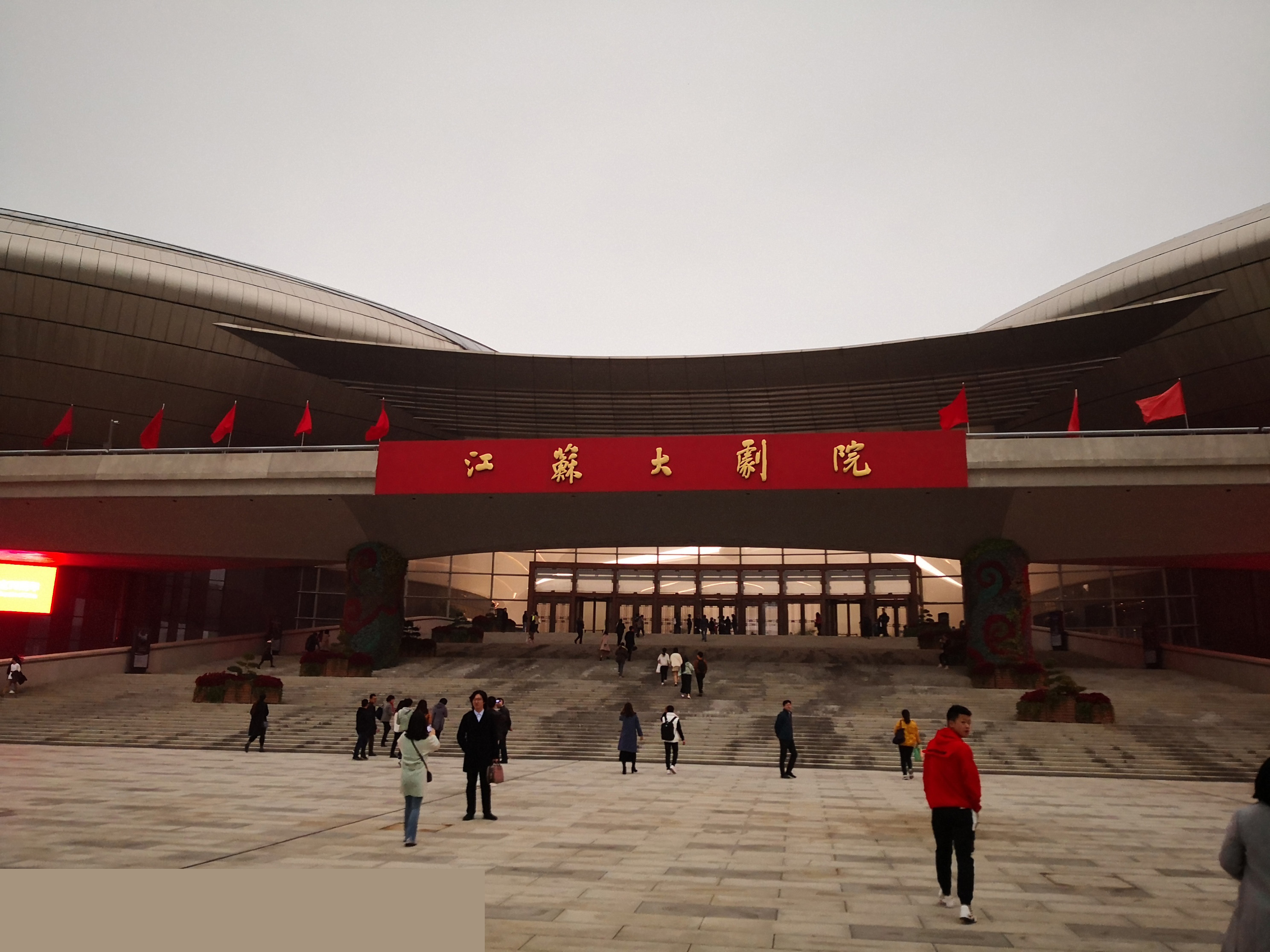

Finally, a comment on the performance site, which was the Jiangsu Centre for the Performing Arts (JSCPA). To my surprise, this is a vast and ultra-modern place, one of the many enormous Western-style performing arts centres built in China in the twenty-first century. JSCPA is sometimes called “four water drops” because there are four big structures looking like water drops in the middle of a vast park. These are the Opera Hall, Concert Hall, Drama Theatre and Multifunctional Theatre. It is extremely impressive, and I think the Jiangsu government must have put an enormous amount of money into it.

The entrance to the Nanjing Opera House

The opera house in this JSCPA is just extraordinary. It is very large, the acoustics are good and the seats comfortable. The entrance is grand with a large flight of stairs, leading from a park up to the opera house itself. The whole place is ultra-clean, including the toilets, and shows the authorities put a high priority on the arts, both in terms of effort and money.

To sum up, to see this performance of Parsifal in such a magnificent theatre in Nanjing was completely unplanned and unexpected. The site was spectacular, the performance excellent and the audience reception, as far as I could judge, very good. Overall, it was a wonderful experience.

[…] A Wonderful Experience: ‘Parsifal’ in an Unusual Place by Colin Mackerras https://wagnerqld.com.au/a-wonderful-experience-parsifal-in-an-unusual-place/ […]