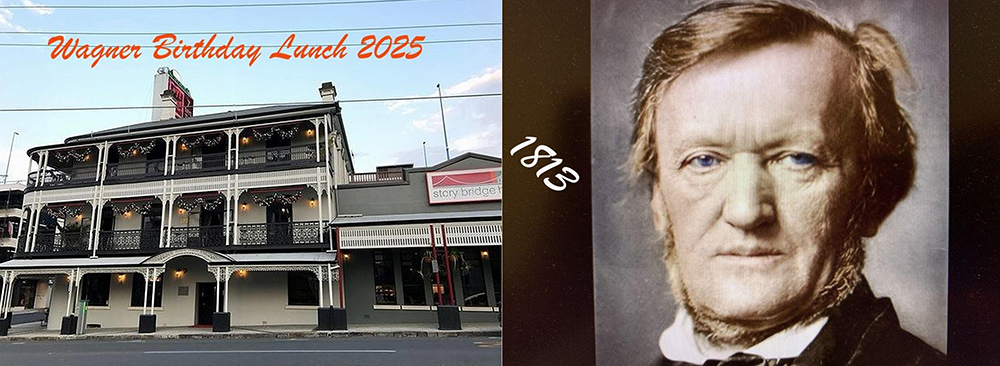

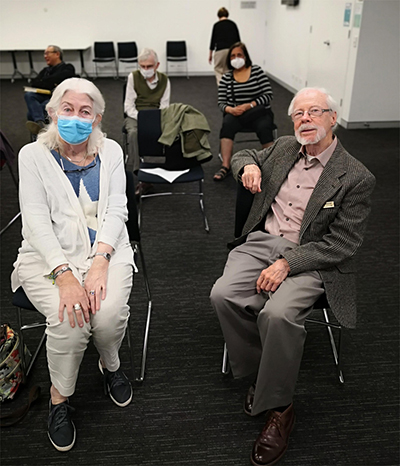

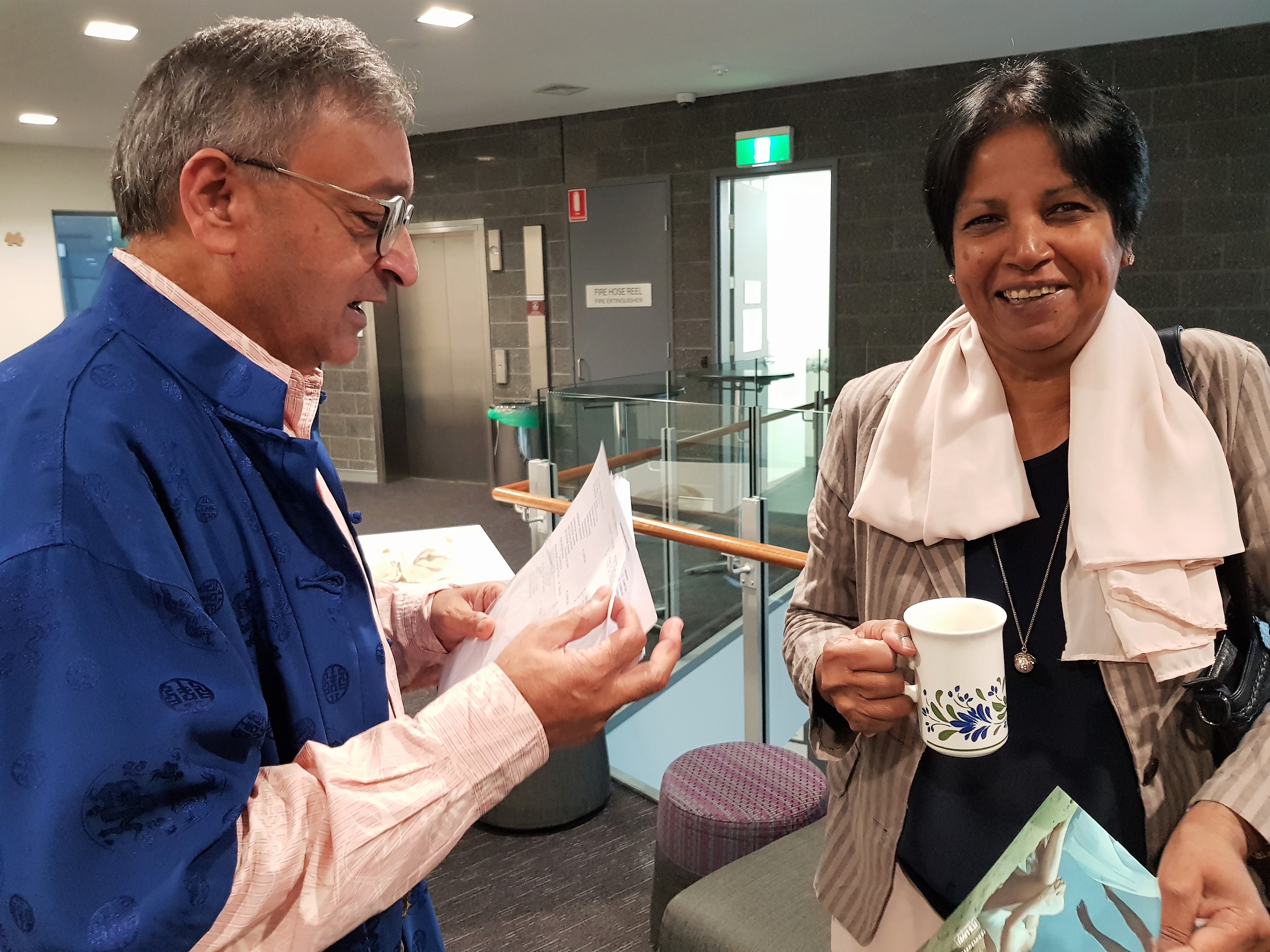

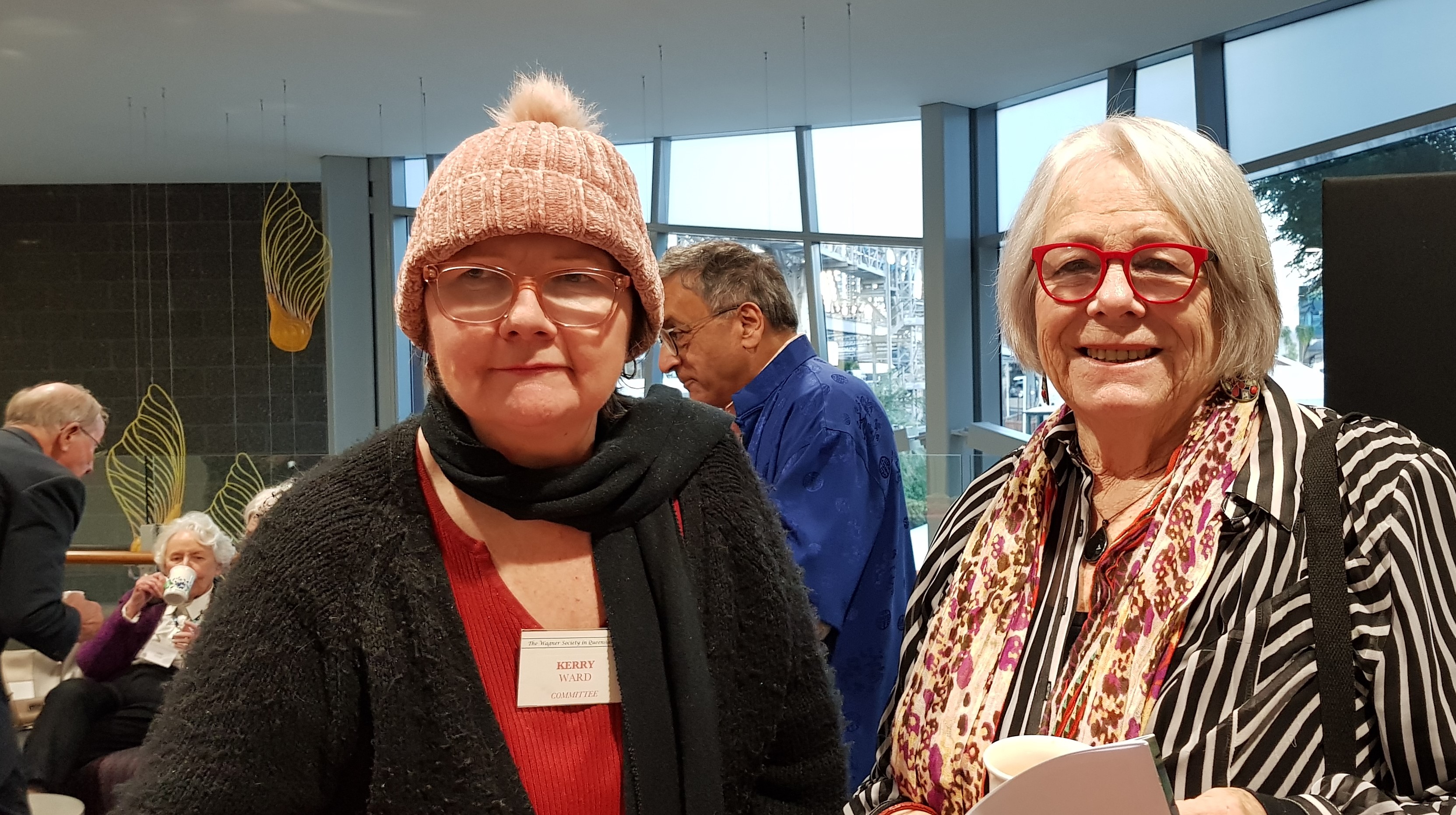

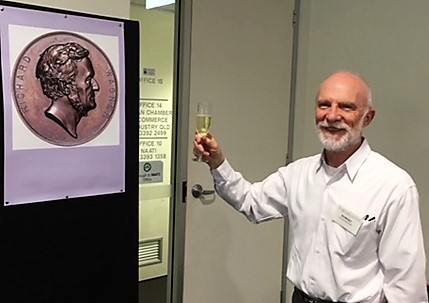

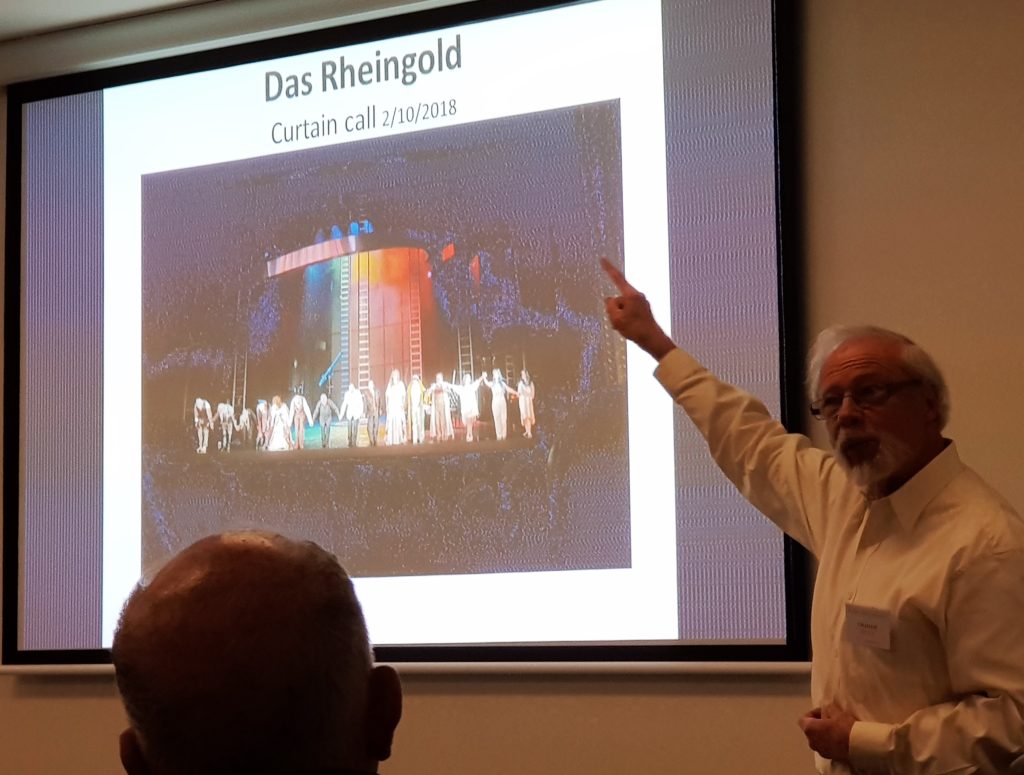

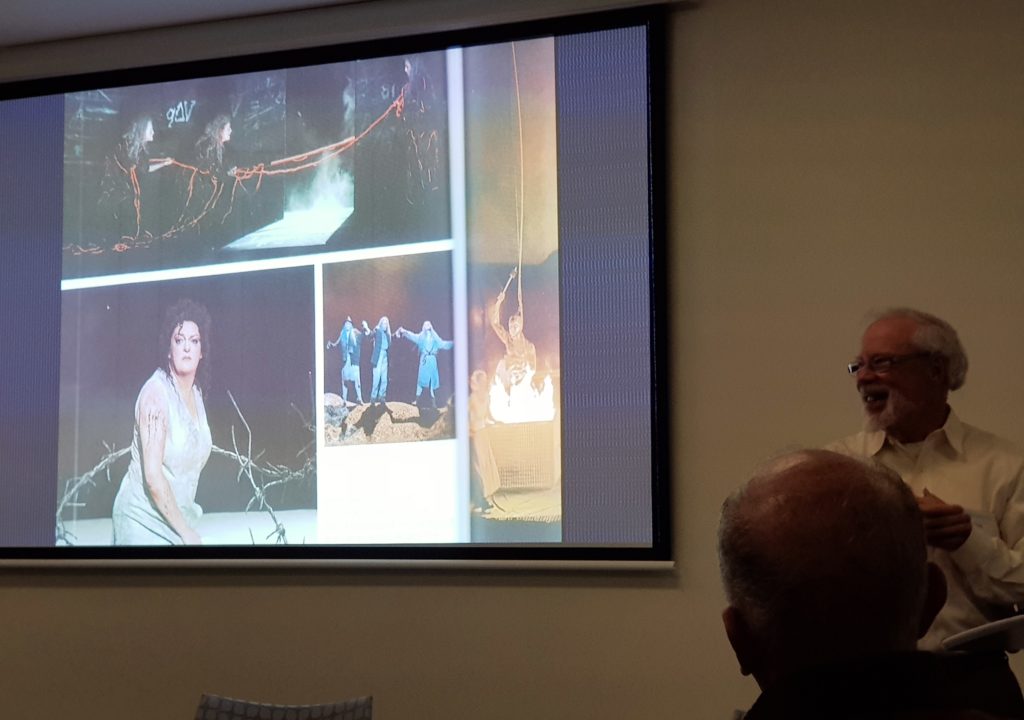

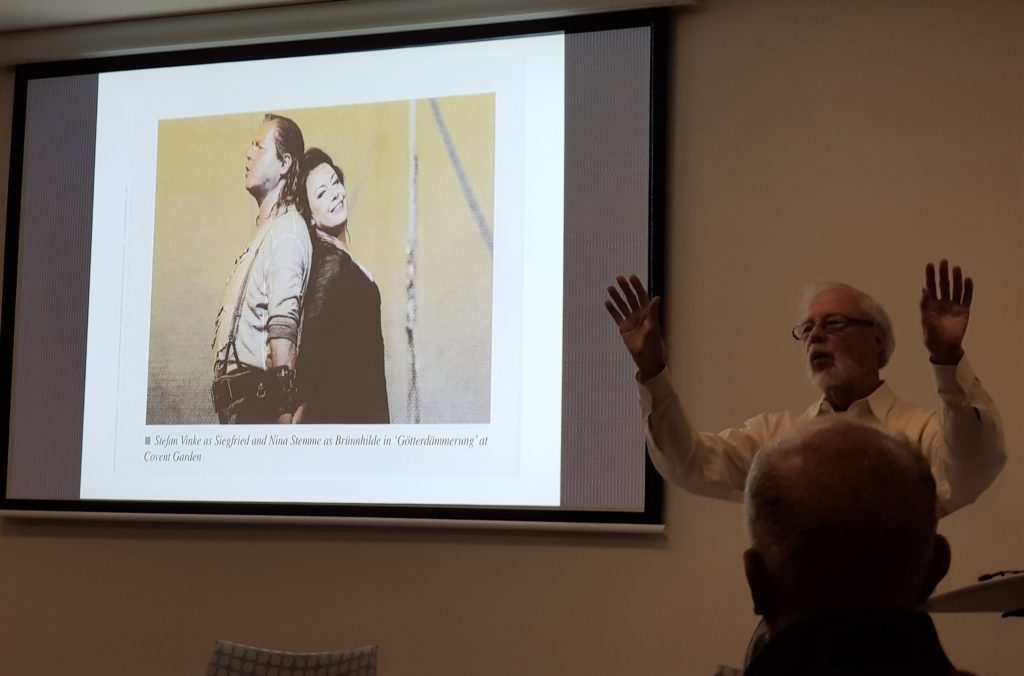

RICHARD WAGNER’S BIRTHDAY LUNCH, AND TALK BY DR MICHAEL JOHN. Saturday 24 May 2025

The Story Bridge Hotel, Kangaroo Point, and Richard Wagner, born 22 May 1813

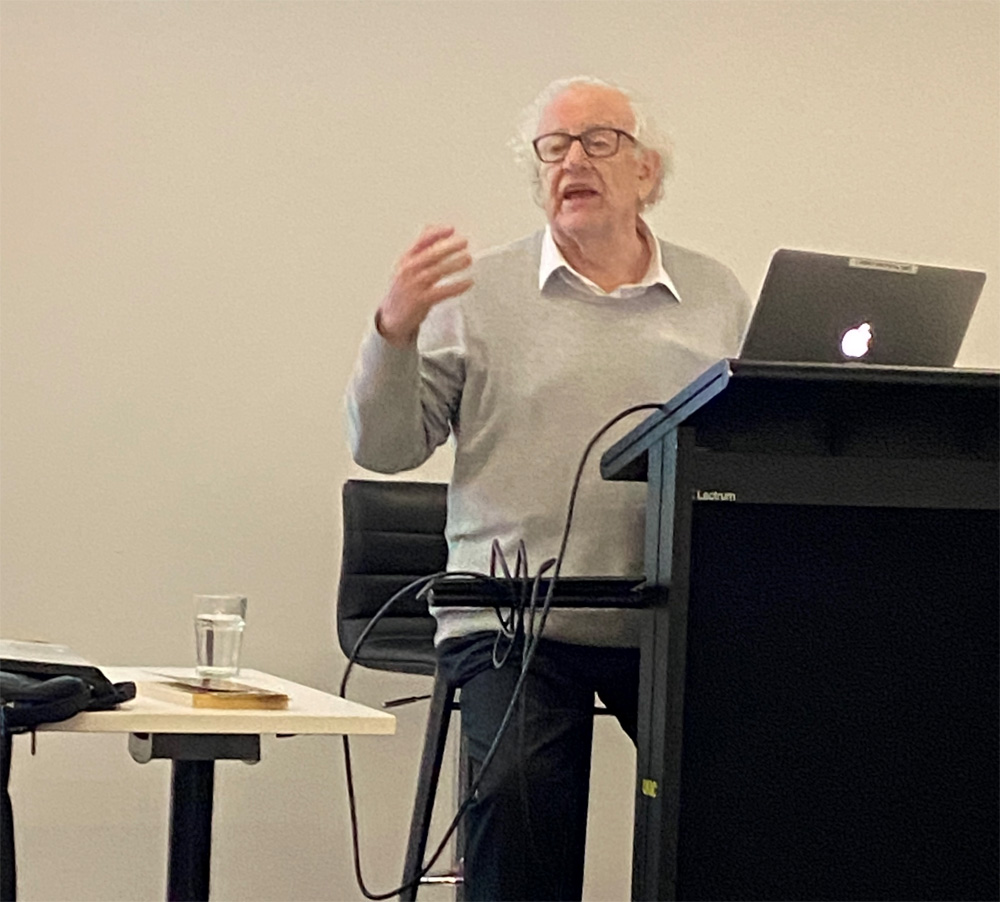

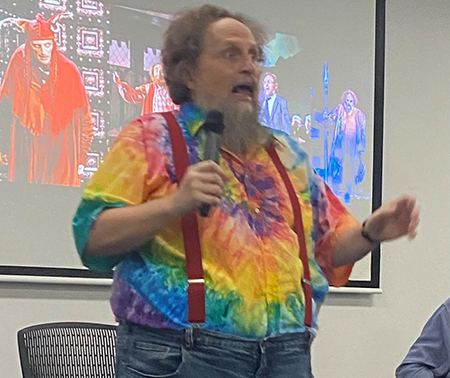

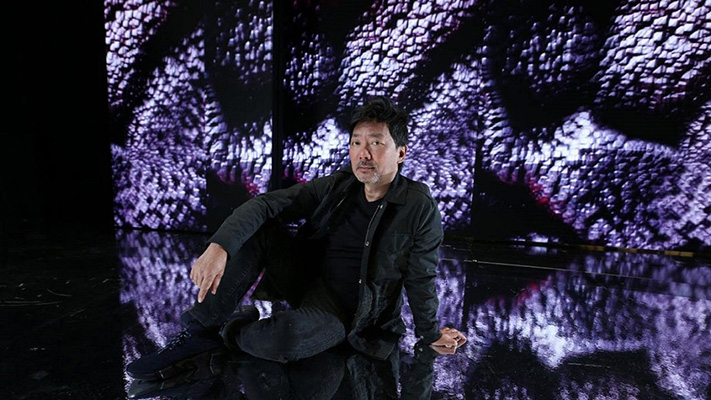

Dr Michael John

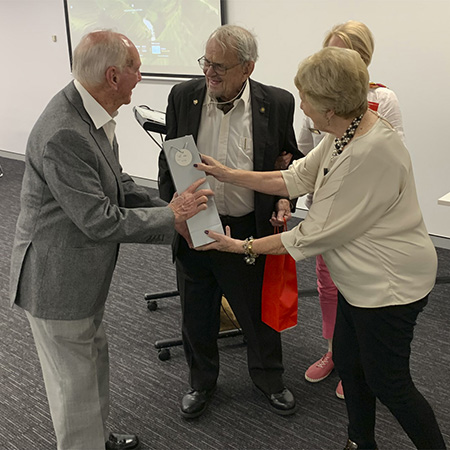

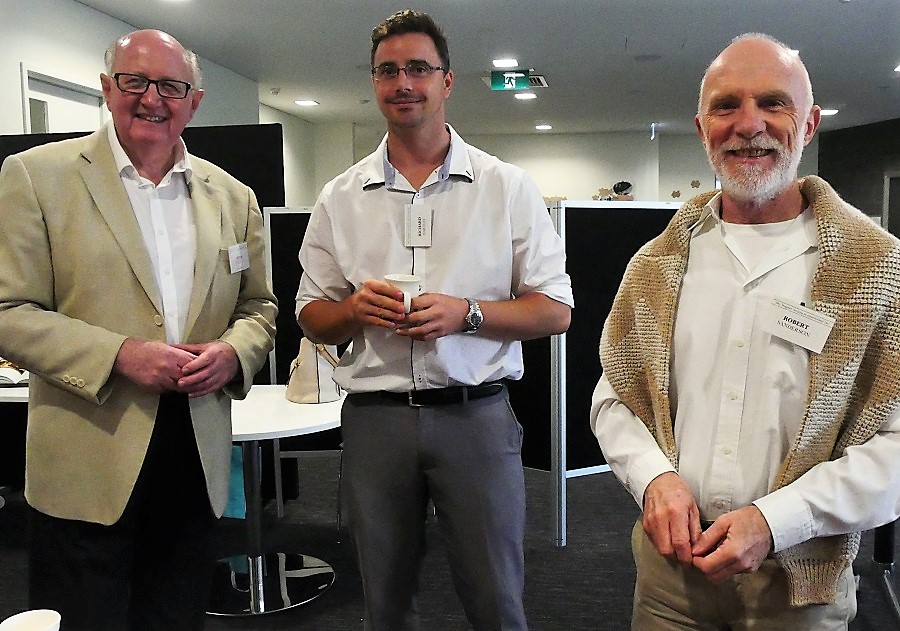

Michael John and his sons Daniel and Ben and our president Peter Bassett

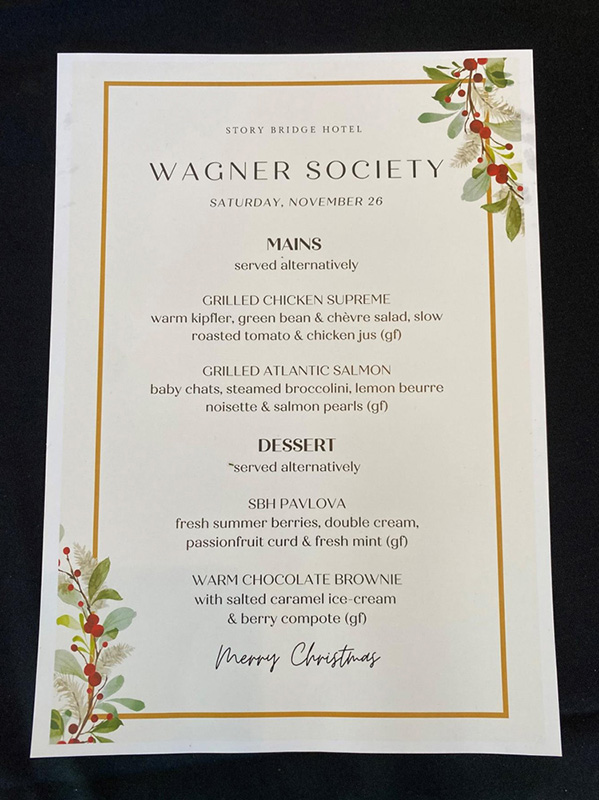

Our Society held a Lunch in the Heritage Room of the Story Bridge Hotel on Saturday 24th May to celebrate the 212th anniversary of the birth of Richard Wagner. Twenty-nine members and their guests enjoyed the delicious lunch which was coordinated by Rosemary Cater-Smith (thank you Rosemary!) and was followed by a stimulating talk by Michael John.

Wagner’s Quest for the Ideal: Music, Drama, and the Poetics of Opera (Some excerpts from Michael John’s presentation)

“Wagner was through and through an artist; he thought, felt, saw and encountered the world as only a committed artist may. It may be argued that music as an art form affects a person more deeply than written or spoken text, a theatre production, or art in the form of canvases or sculpture. Wagner’s clear intention in his mature operas was to summon intangibles to present themselves as fully as may be possible through the medium of an aesthetic totality composed of music, singing/libretti, acting and staging.

Wagner undeniably was an arch Romantic, a bold voyager on a radical critical adventure in sublime art to embrace the realm of the Gods, a journey informed additionally by his classic idealism which privileged the golden age of Hellenic Greek culture and the misty, dark deep woods of Germanic folk tradition. We might profitably unpack some relevant considerations regarding a critical poesis from the writings of Wagner’s Irish contemporary, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and, in particular, his theory of poetic form.

In Hopkins’ eyes poetry may be qualitatively differentiated from ordinary language by its structure or artifice. Poetry is a kind of language frequently distinguished by structural regularities, patterned sound (rhyme & metre) and semantic content. Here we encounter the aesthetic principle of ‘inscape’, the actual rhyme and meter of a babbling, gurgling, splashing Irish rivulet must sing forth from the stress in the language of the recited poem. Anyone even cursorily acquainted with The Wreck of the Deutschland, Hopkin’s most formally perfect poem, a monumental poem which lurches and surges over 280 lines telling of the death in swirling winter foam of five Franciscan Nuns who drowned in those horrid hours when the foundered Deutschland slowly broke-up between midnight and morning of December 7th 1875, will have no perception of an ongoing counterpoint in sprung rhyme with the distribution of stresses in its 35 stanzas. Hopkins’ theory of poetic form, which he sought to perfect in his works, is that the more highly and intricately structured a work is, the more it will appear to have no structure at all.”

Photography Jennifer Lawrence and Marion Pender

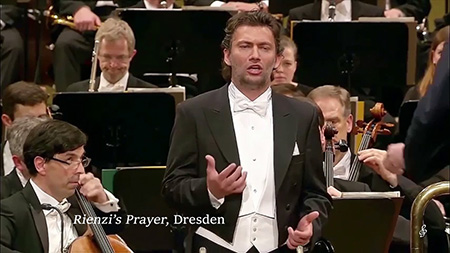

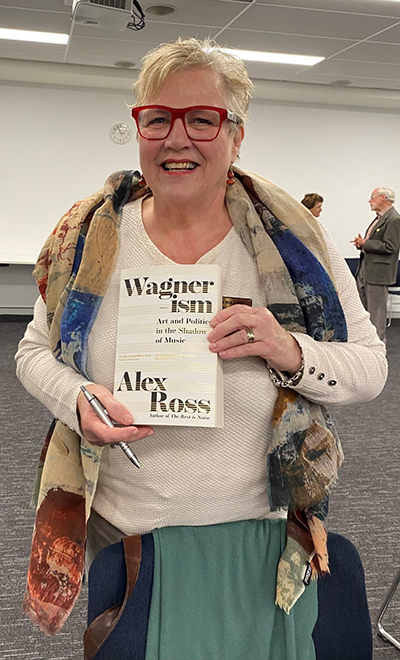

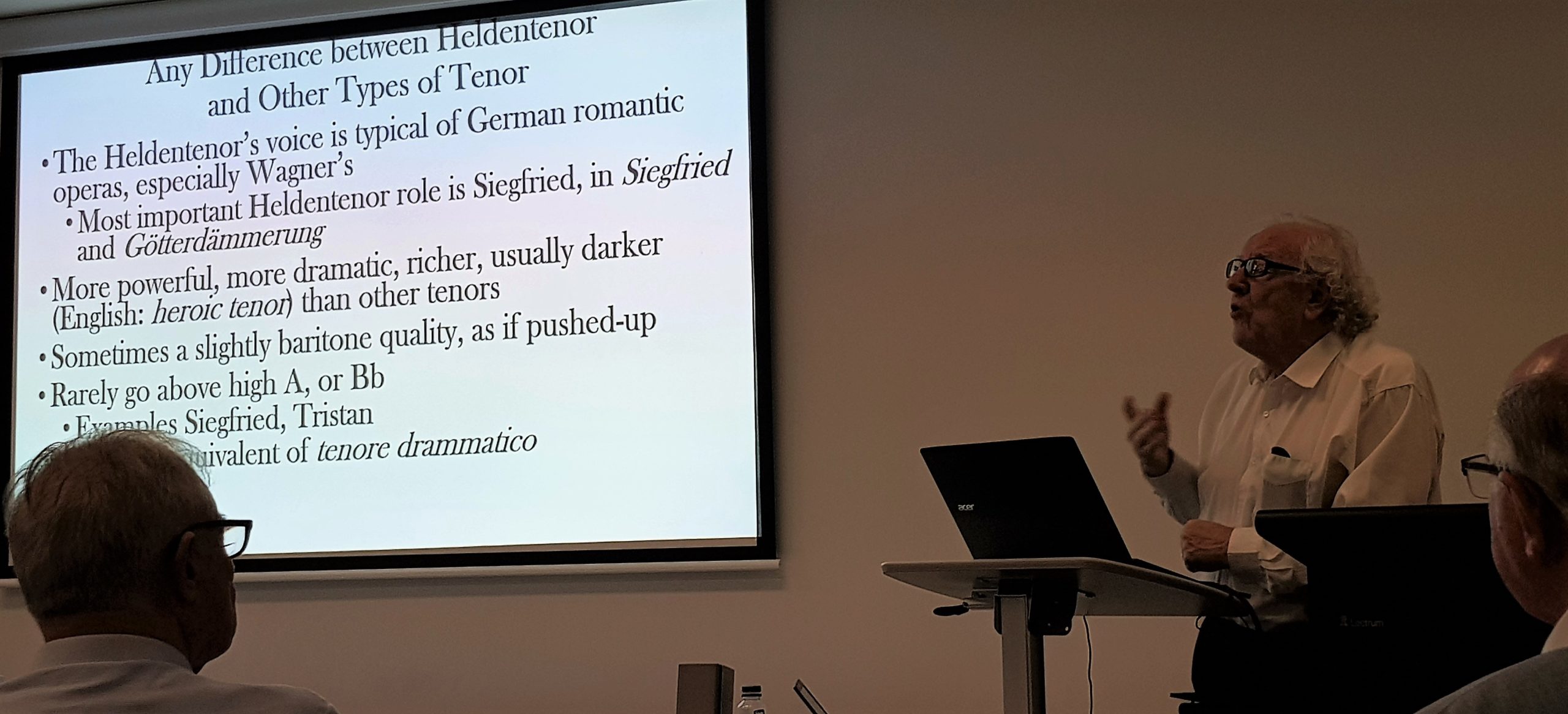

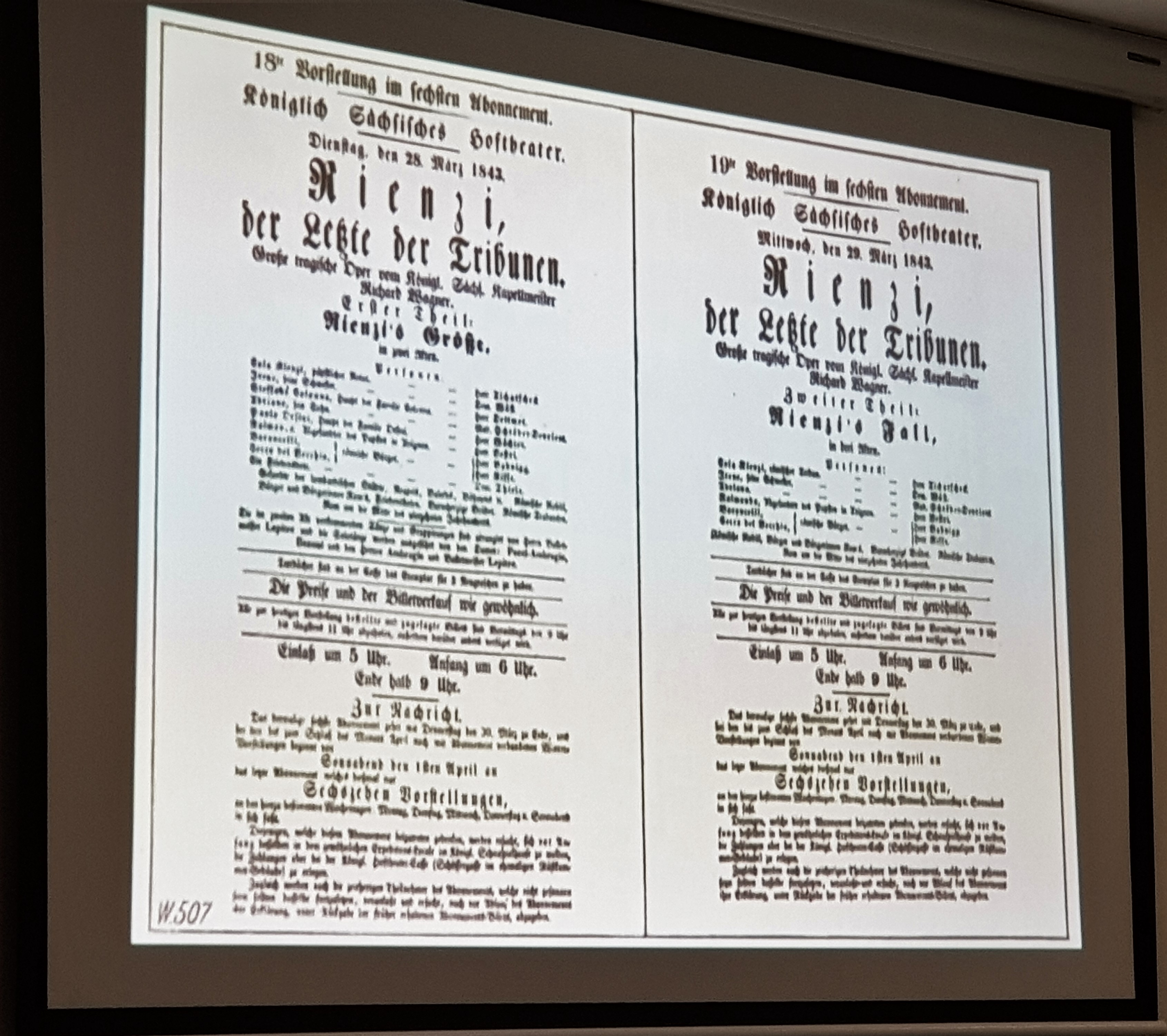

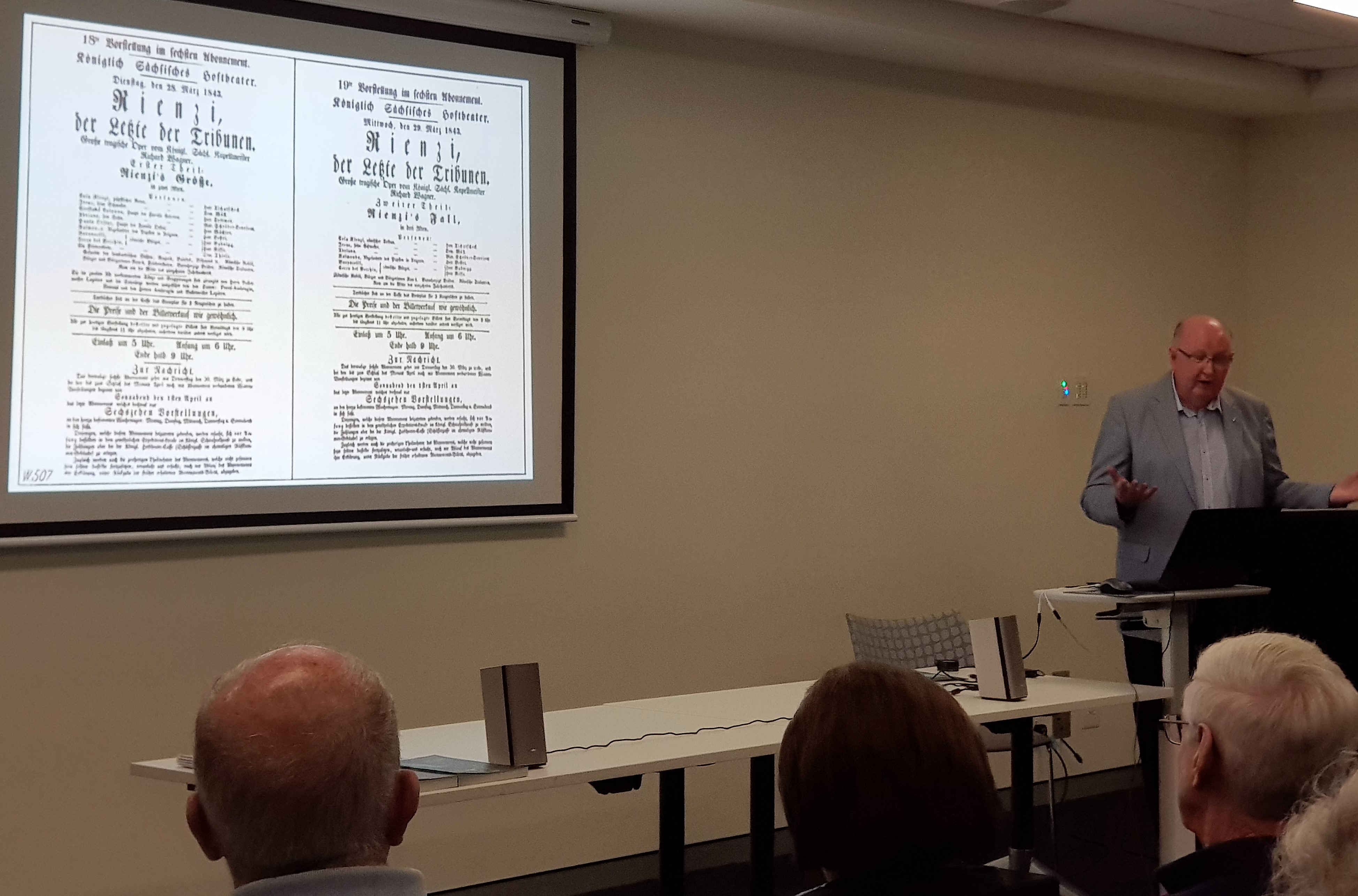

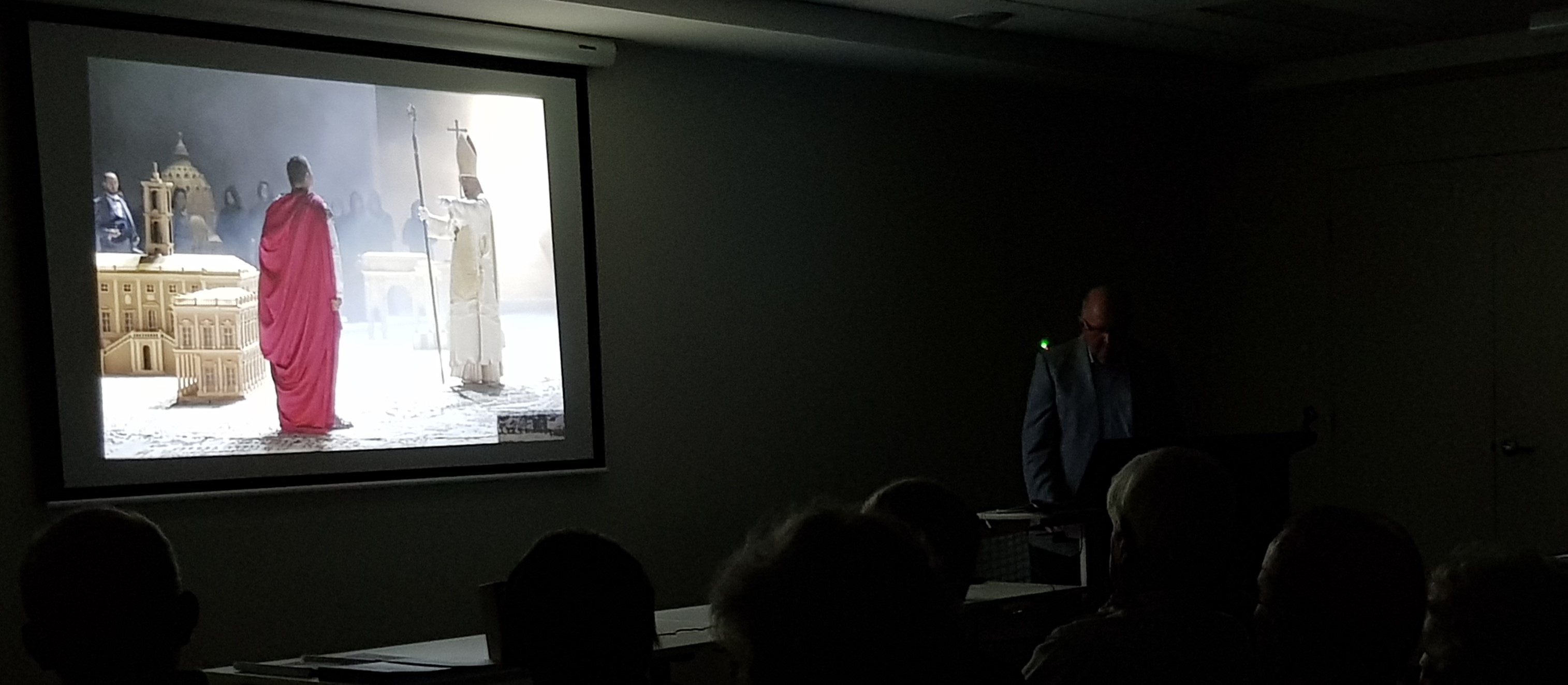

RICHARD WAGNER AND THE ART OF SONG BY PETER BASSETT. Saturday 29 March 2025

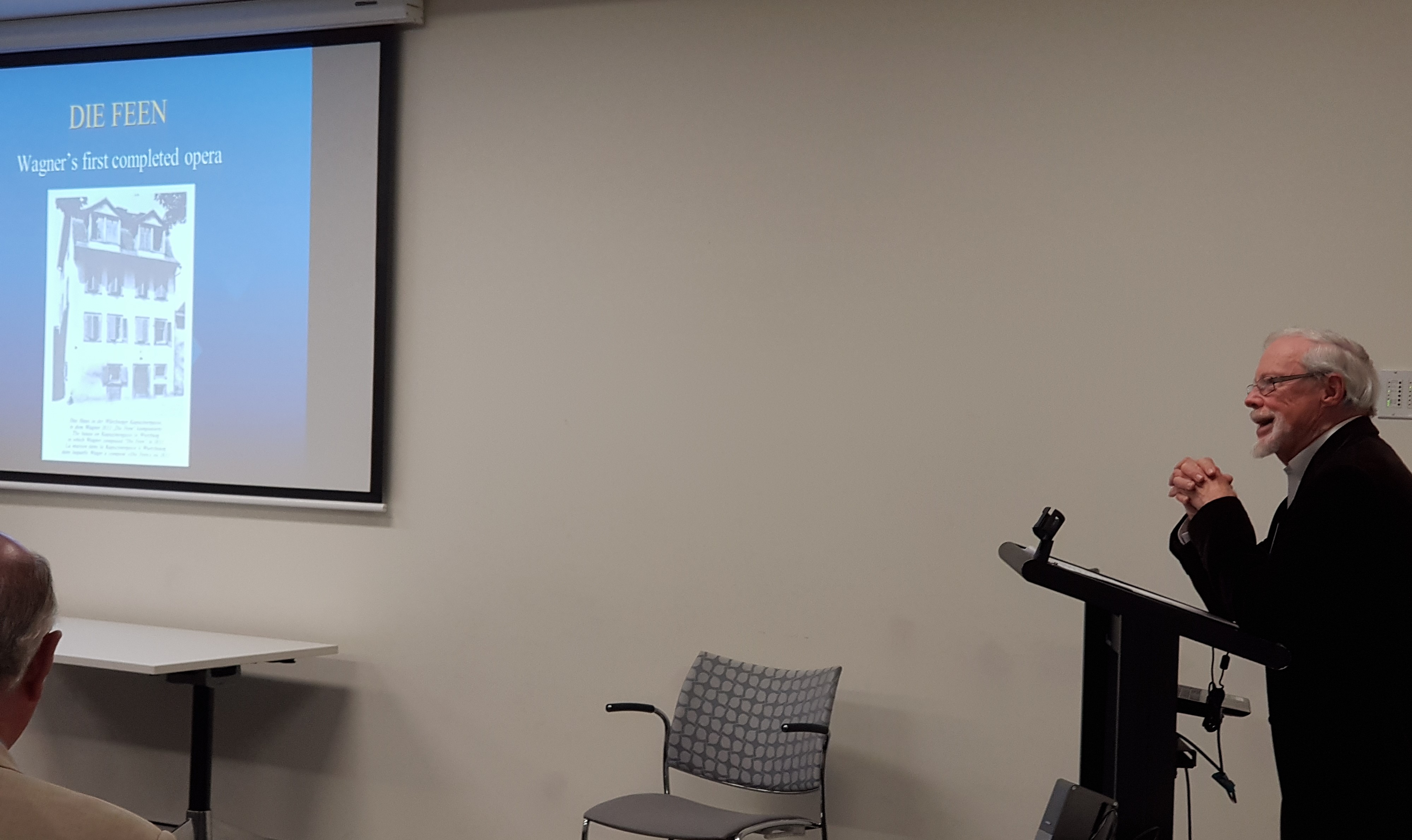

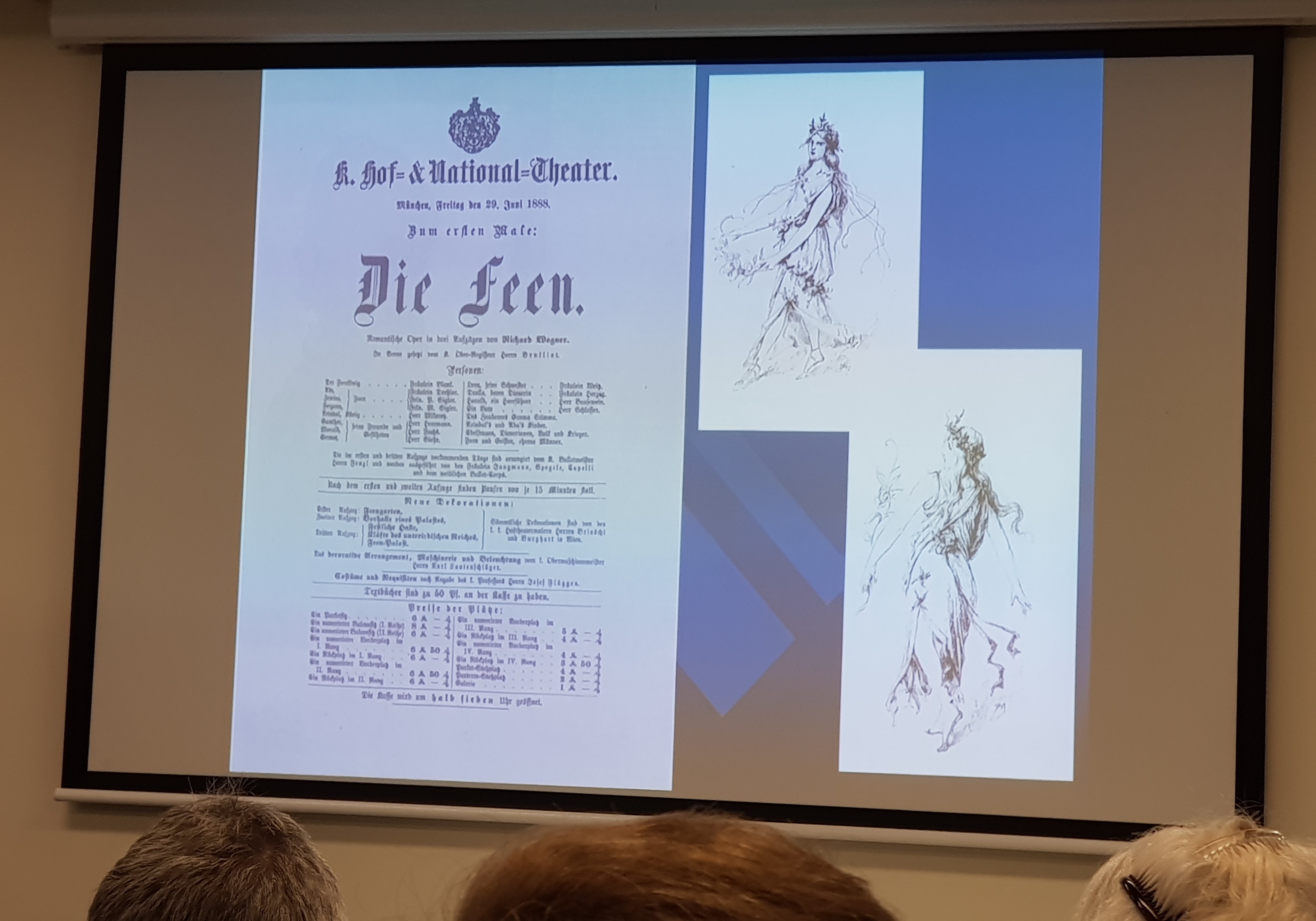

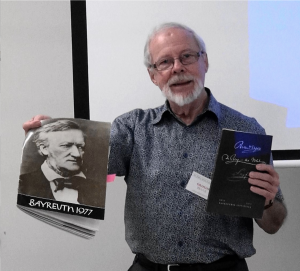

This brilliant talk by our President Dr Peter Bassett (hereafter Peter) was fascinating not only because of its subject and style of presentation but because it was filled with relevant pictures and many wonderful musical excerpts.

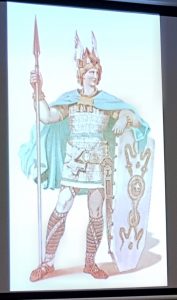

These illustrated the topic of the talk which was how Wagner developed in his way of treating the human voice, which he regarded as the premium musical instrument. The main point of Peter’s talk was the importance of singing and the art of song throughout Wagner’s career from his earliest opera Die Feen (The Fairies) [shown above] through to his last, Parsifal. His stress was on how Wagner’s process of development in song showed his genius as a composer and innovator. But the range of singers was also great, from all periods, but also all ranges, soprano, mezzo, tenor and baritone.

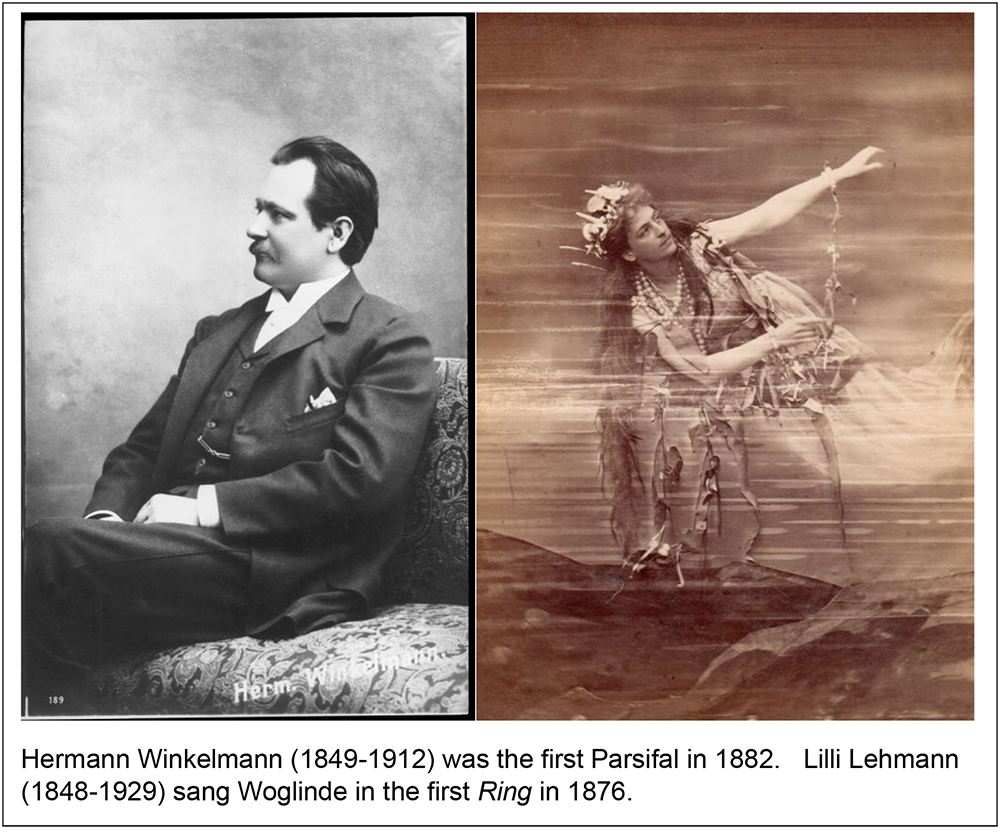

The talk began with examples of singers who had actually been active in Wagner’s time. Though sound recording was not invented until after Wagner died, there are still recordings of singers known to Wagner or who sang in Wagner’s time. For example, Hermann Winkelmann who premiered the role of Parsifal in 1882 made a still surviving recording from 1905.

Winkelmann’s fine voice was exemplified in the Prize Song in Die Meistersinger, accompanied by a piano, not an orchestra, but it showed us the quality and strength of Winkelmann’s voice. The famous Lilli Lehmann, not to be confused with the later Lotte Lehmann, made a still surviving recording in 1907. Peter collected these when in Germany and they still give us a fascinating glimpse into the earliest singers of Wagner’s music.

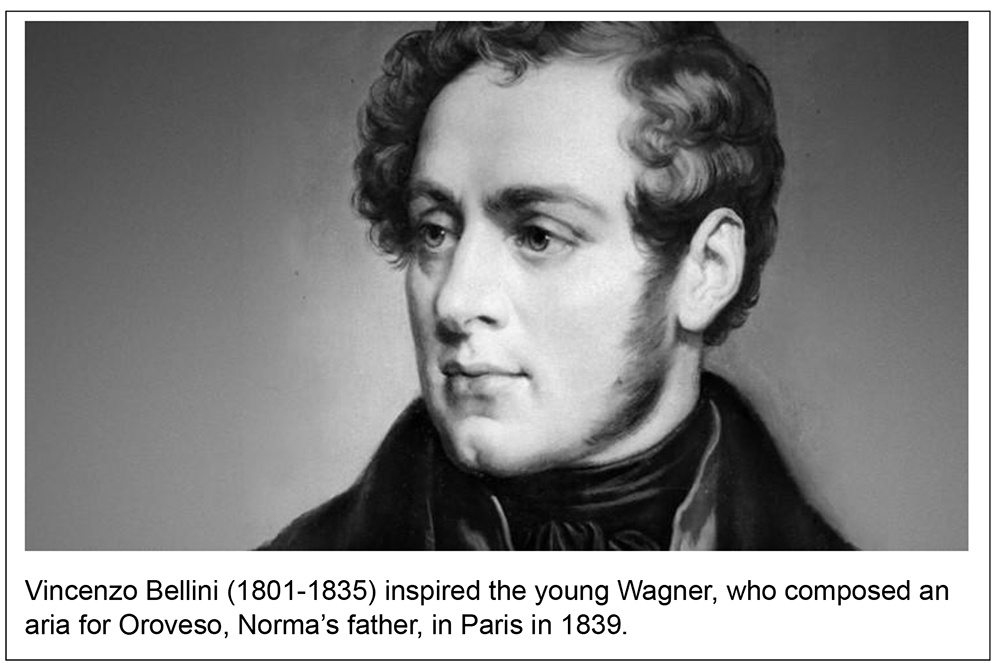

What made this talk so interesting was Wagner’s development from earlier in his life, when he took Italian Vincenzo Bellini as his model, to the mature Wagner who changed music with his epoch-making and highly original Trisan und Isolde, to his last work Parsifal.

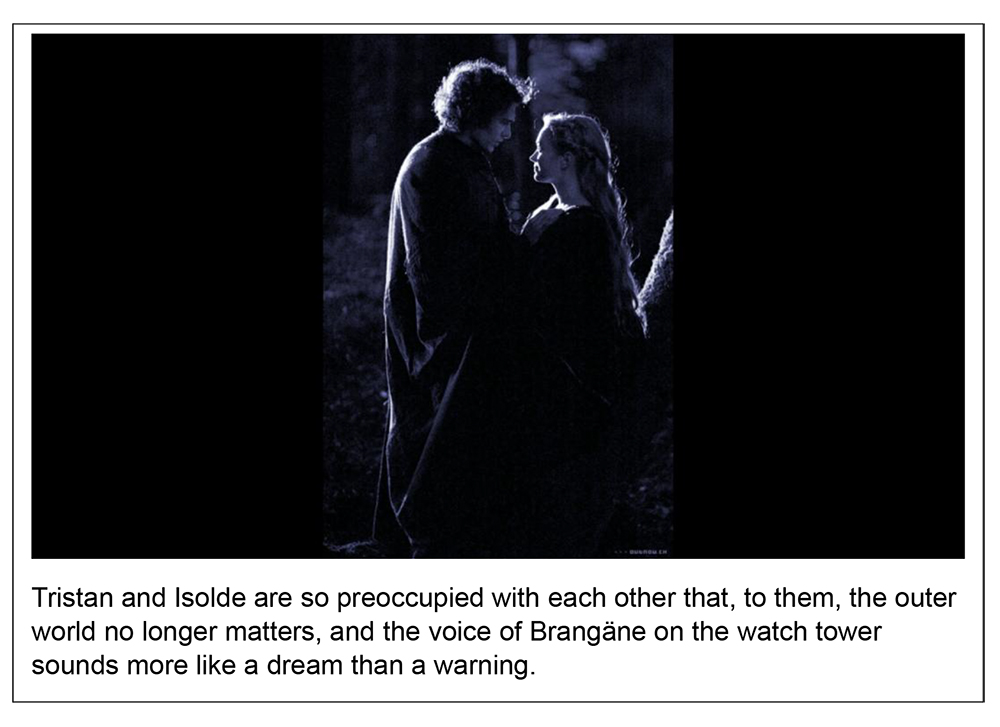

The musical illustrations were too numerous to list. One that struck me with particular force was Peter’s reference to the marvellous Wilhelm Fürtwängler recording of Tristan from 1952, which featured also Kirsten Flagstad as Isolde and Ludwig Suthaus as Tristan. He said listening to this recording as a youth had changed his life through its magnificence and through its exposure of the wonderful, epochal work that is Tristan, and through it to Wagner in general. I would like to add, on a personal note, that I bought this recording very soon after it came out and was similarly affected by this wonderful music and recording. The excerpt he played was Brangäne’s warning from Act II, with Blanche Thebom singing. This extremely innovative music has a unique dreamlike quality about it, with innovative harmonies and the kind of sound never heard before. And Brangäne’s last words “Schon weicht dem Tag die Nacht” (“Soon night will give way to day”) shows its expression of night, and connection with love! What music this is!! I have even heard it claimed as the most beautiful music ever written.

Another illustration was the last pages of Parsifal, also among the most beautiful music ever written. Peter’s comment was that singing was still central to Wagner even in passages that are mainly instrumental. After all, a chorus sings “Erlösung dem Erlőser” (Redemption to the Redeemer) even after Parsifal has sung his last notes.

Peter’s vast scholarship on Wagner and clarity of presentation, together with many excerpts of really beautiful music, the great majority illustrating stages in Wagner’s approach to singing, made this an uplifting, fascinating and wonderful talk.

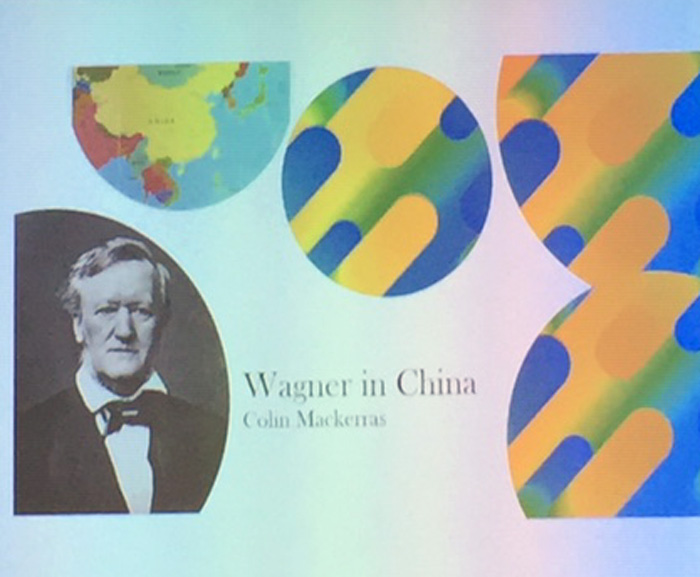

Observations by Professor Colin Mackerras

Meeting photography by Judy Xavier

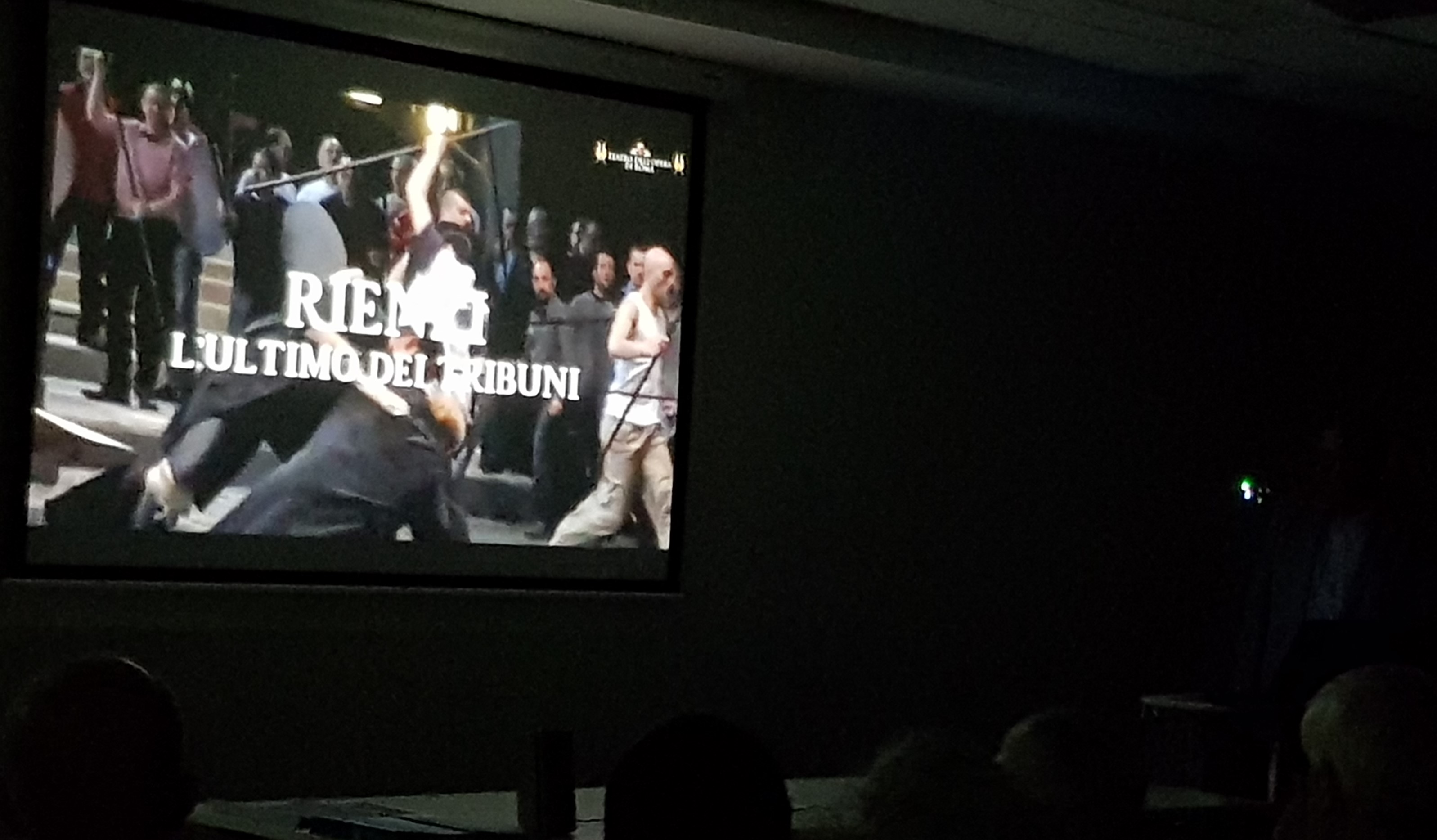

PARSIFAL REANALYSED BY PROFESSOR COLIN MACKERRAS. Saturday 15 February 2025

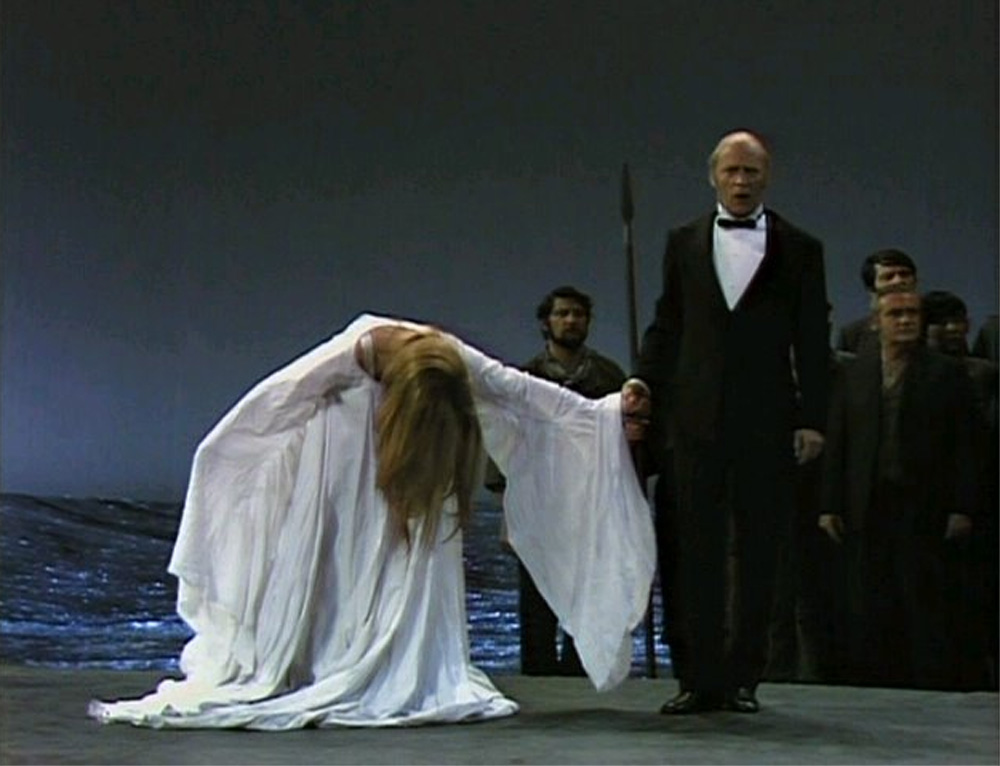

Some forty WSQ members and guests were treated to a masterful presentation by Prof Mackerras (hereafter Colin) which commenced our lecture series at the reclaimed venue of 4MBS. The orientation of Colin’s address was to surmount the diehard humbugs of antisemitism and blasphemy not infrequently directed at Wagner’s last opera, and, achieving this, from the standpoint of ‘redemption’ to consider the philosophical and spiritual fabric of this mighty work as conveyed by its music as much as the libretto. Certainly, no small feat given the allotted time of seventy minutes, even for an accomplished scholar.

Structurally, Colin opted to stretch members’ processing capacity with twenty-seven PowerPoints, each made-up of around six detailed dot points, such that the lecture was guided into three long excerpts of music – no mean feat. Colin traversed this material with pivotal excerpts from the libretto as sung in German, and here his fluency, emphasis and passion greatly aided grasping key features of the opera’s plot. Wagner defined his masterpiece as a ‘Bühnenweihfestspiel’ – a stage consecration festival drama – and moreover, defended the work from accusations of being puritanical on sex and sacrilegious (Nietzsche – Robert Greenberg was worse still!) by stating that ‘art saves the spiritual value, it doesn’t represent religious allegories being the composer’s invention’. Interestingly, the Nazis (never known for insight) wouldn’t allow the opera’s performance as they judged it too pacifistic. Having demolished the misanthropic charges of humbugs, Colin leant into the conceptual fabric and frequently sublime music of Parsifal.

Compassion and forgiveness, the twin elements of redemption. Here consummate Soprano Frida Leider is Kundry; ‘Ich Sah das Kind’ lilts forth in smooth marshmallow tones as she seeks to seduce our innocent fool. Having thus enchanted her prey, she seeks his damnation with ‘the first kiss of love’, manoeuvring a mother’s mortal longing for her lost son into the wanton embrace of sexual abandonment. ‘Nein! Nein!’ Parsifal cries forcefully with agonised remembrance of Amfortas, ‘Redeemer save me from this woman’. Colin held us spellbound. The curse is broken, innocence is lost and Parsifal sees the world clearly. While consumed herself with longing for redemption, Kundry, condemned to endless transmigration of her soul through her mocking of Christ, remarkably refuses Parsifal’s bargain to bestow this miracle simply in exchange for her guidance back to the Grail’s sanctuary.

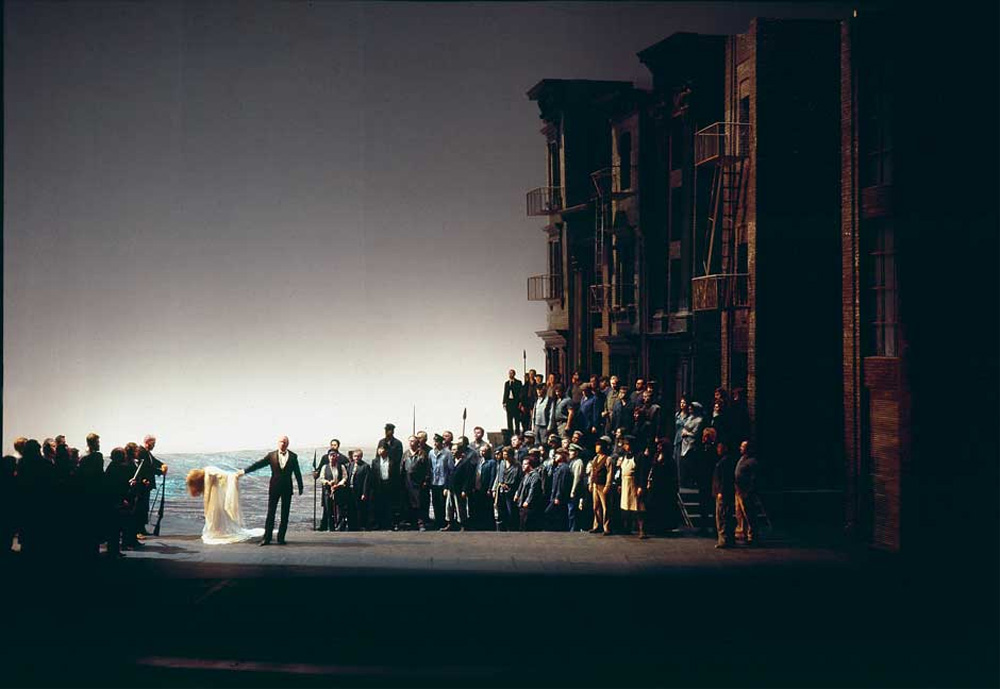

To depressurise members, Colin moved us to Act III, Good Friday, and the melodious, spiritually-swooning duet between Ludwig Weber (Gurnemanz) and Wolfgang Windgassen (Parsifal) – Bayreuth, 1951 – as the new Grail Knights’ King is anointed, and then into the exquisite music of the final scene (Met production) where Kundry, in her dying gratitude, reaches her hands towards Parsifal with the Grail.

Observations by Michael John

Photography by Cathie Duffy and Jennifer Lawrence

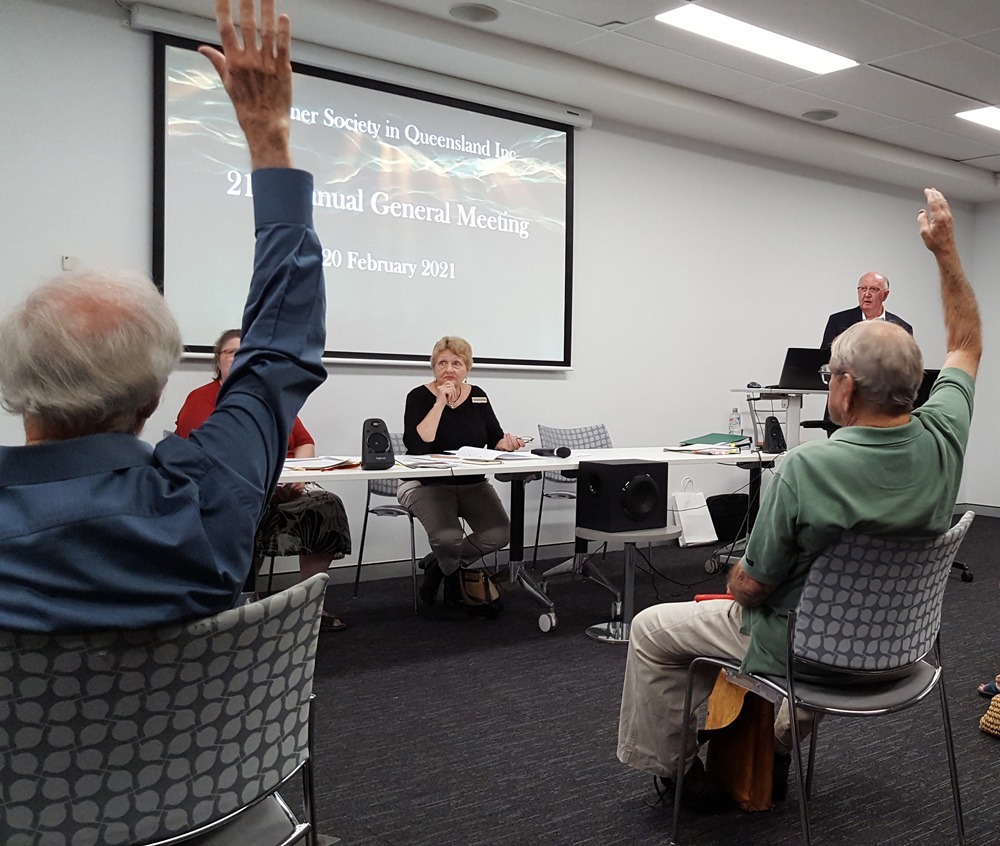

WAGNER SOCIETY AGM & RECITAL. Saturday 30 November 2024.

Our final meeting of the year began with the AGM for 2024, which thanked Rosemary Cater-Smith for her dedication and service as President, and welcomed the 2025 Committee led by President-elect, Peter Bassett. This was followed by our traditional Christmas party with a special added treat: violin and piano arrangements of selections from Wagner’s work performed by Warwick Adeney (former concertmaster of QSO who effortlessly segued between violin and viola) and Stephen Emmerson. They played an already-existing version of the Prize Song from Die Meistersinger; Träume, the final song of the Wesendonck Lieder – unmodified except that Warwick’s viola took the place of the voice, and Stephen’s new arrangements of two scenes from Die Walküre: Sieglinde’s narrative from Act I and the Magic Fire Music from the very end of the opera.

It might have seemed a rather quixotic thing to arrange Wagner’s eloquent orchestral narratives for the duo format. But, as Stephen noted in his introductory comments, this was a common thing before the age of recordings, indeed arrangements played as house-music would have been how many people discovered the music. And it was fascinating and magical. If the Meistersinger Prize song sounded a little like salon music, perhaps this was how the music was commonly refracted in the home. In contrast, the eloquence of Träume and the Walküre extracts was direct and moving in the performances. Especially striking was how well the viola worked substituting for Sieglinde. It was a wonderful way to celebrate the end of 2024.

Observations by Alpha Yap

Photography by Cathie Duffy and Jennifer Lawrence

THE FLYING DUTCHMAN – COMMENTARY AND ANALYSIS by Peter Bassett. Saturday 19 October 2024.

For the text of Peter Bassett’s talk, please click here to download pdf.

Tour de force: Der fliegende Holländer, Dr Peter Bassett

Peter loosely structured his lecture around three domains of interest: (i) The opera’s presented content; (ii) the characters’ psychological machinations, and (iii) fate or forces beyond human control. My lecture commentary will follow suit. As members have come to anticipate from Peter, he comprehensively traversed the opera’s three acts with seven selected excerpts of duets and arias to counterpoint the deeper themes being played out: Daland’s desire for a win/win outcome (wealth and a married daughter), Senta’s belief in her higher-purpose (redemption of the Dutchman), Erik’s tedious pedestrianism, and the Dutchman’s longing for peace through eternal oblivion. Clearly much more than a poignant potion for tragedy. I might mention additionally Peter’s attention to the condemned crew of the Flying Dutchman’s ship, confused and wretched ghosts who wrote letters to long-dead loved ones at home.

Regarding the opera’s psychological insights into Wagner’s mind, Peter built the case that, indeed, Wagner was a Dutchman-like driven genius, making landfall only periodically (releasing a new work) and then setting sail for an idealised new creation to contain his music and dramatic artistry. Allied to this thesis, Peter highlighted the familial deaths (especially his beloved older sister) and emotional longing which blighted Wagner’s early development, and hence, moreover, Wagner’s need of assured women who, in turn, he could idealise. Hence, Peter revisited the standpoint of ‘the eternal feminine’ infusing the Wagnerian ‘total aesthetic’. Fascinatingly too, Peter supported the understanding that Wagner’s Paris experiences with his influential predecessor Giacomo Meyerbeer were at the root of Wagner’s later distinctive antisemitism.

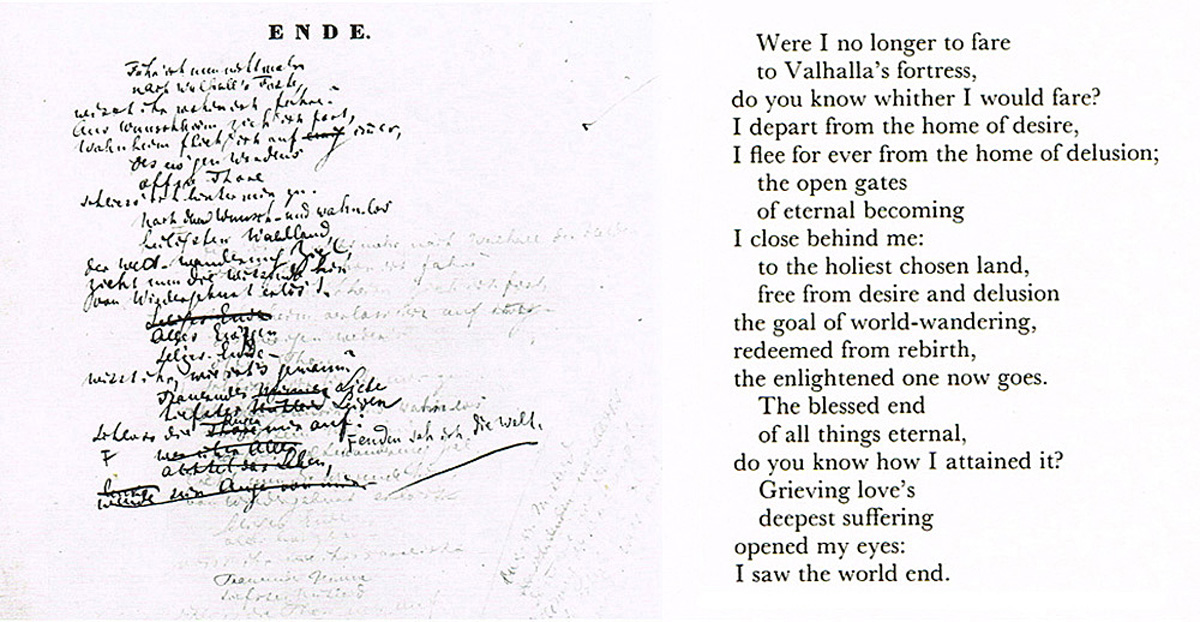

Finally, what does Der fliegende Holländer reveal about Wagner’s philosophical historicity? We plainly see oblivion overturned by faith leading to transfiguration; the way is thus open for a more sophisticated analysis of apparent human reality as captured particularly with Tristan und Isolde (with a big shout-out to Mathilde Wesendonck). So, is it an esoteric sensibility which we commonly represent under the umbrella term ‘love’ which best epitomises the total aesthetic of drama and music quested for by Wagner? It’s a working hypothesis certainly, and yet we are ourselves haunted by the closing scene of The Ring, a tranquil Rhine perhaps depicting a force above gods or fate … we feel its presence.

Observations by Dr Michael John

Meeting photography by Jennifer Lawrence

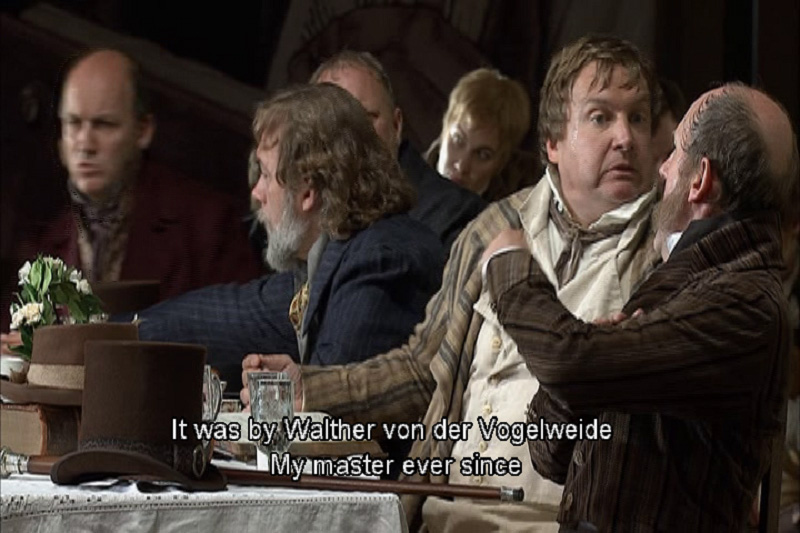

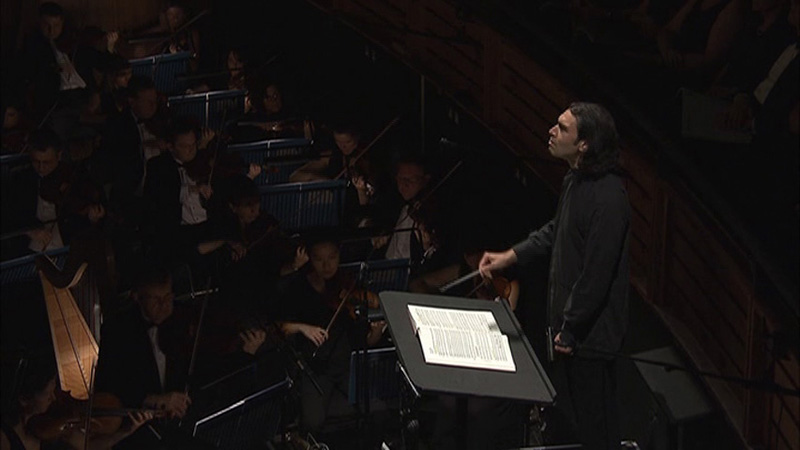

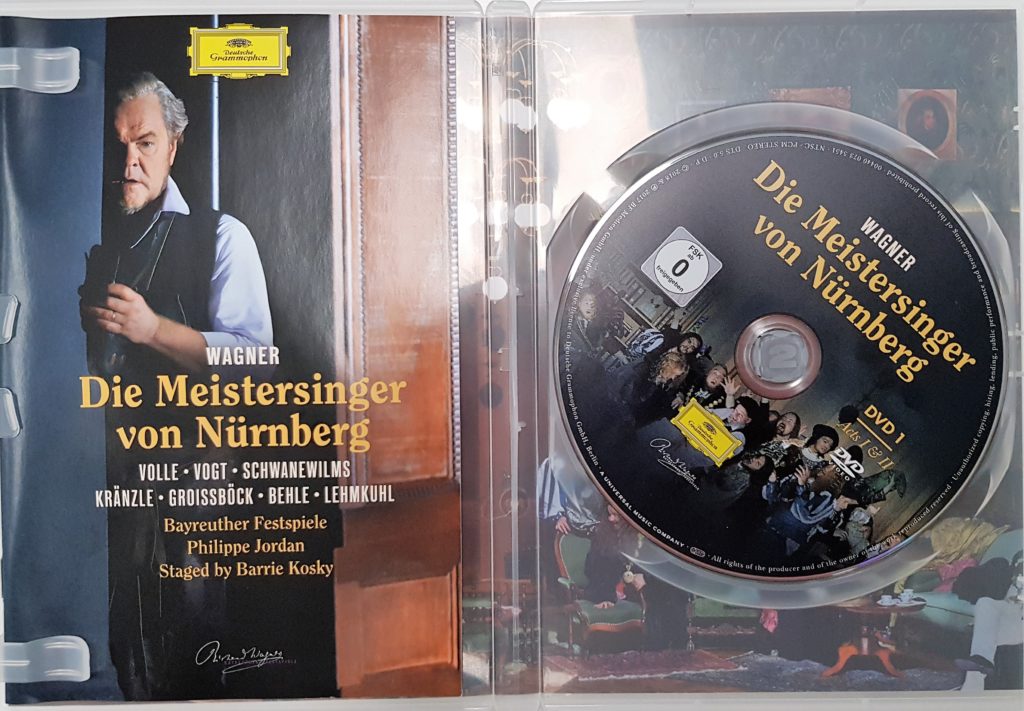

MOVIE AFTERNOON – DIE MEISTERSINGER GLYNDEBOURNE PRODUCTION – Elizabeth Picture Theatre. Saturday 21 September 2024.

“New is my heart, new my mind, new is everything I do.” (Walther von Stolzing)

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg Prelude

The orchestral prelude begins with a broad, confident theme of the guild of Mastersingers and their dedication to Nuremberg and to the arts of poetry and music.

The lyrical second theme, with its hint of impetuous ardour, is a foretaste of Walther’s prize song. It gently ruffles the prevailing mood of self-satisfaction.

Doubts are swept aside by the third theme, a magisterial fanfare derived from an authentic Mastersinger melody of the 16th Century. The guild draws strength from its traditions and from its patron, the harpist and poet King David – a connection emphasised by the prominent use of the harp throughout this passage.

A fourth theme emerges – a soaring expression of the Mastersingers’ devotion to poetry and music, which leads directly into a fifth theme – the final melody of the prize song expressing Walther’s love for Eva. The implication is clear (to the composer if not to the Mastersingers at this stage) – those who value art should be willing to embrace new forms if these flow genuinely from the heart.

All five themes and related motifs burst into a flowering of different ideas and feelings until the first, third and fifth combine in counterpoint to express the unity of the old and the new. The fourth theme with its soaring paean to poetry and music returns to put its seal on all that has gone before, and to bring the prelude to a radiant close.

Description of the Prelude from Peter Bassett’s eBook on Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, provided with the author’s compliments to all members of the Wagner Society in Queensland and to Melbourne Opera to use in connection with their forthcoming production. See: www.peterbassett.com.au

—————————–

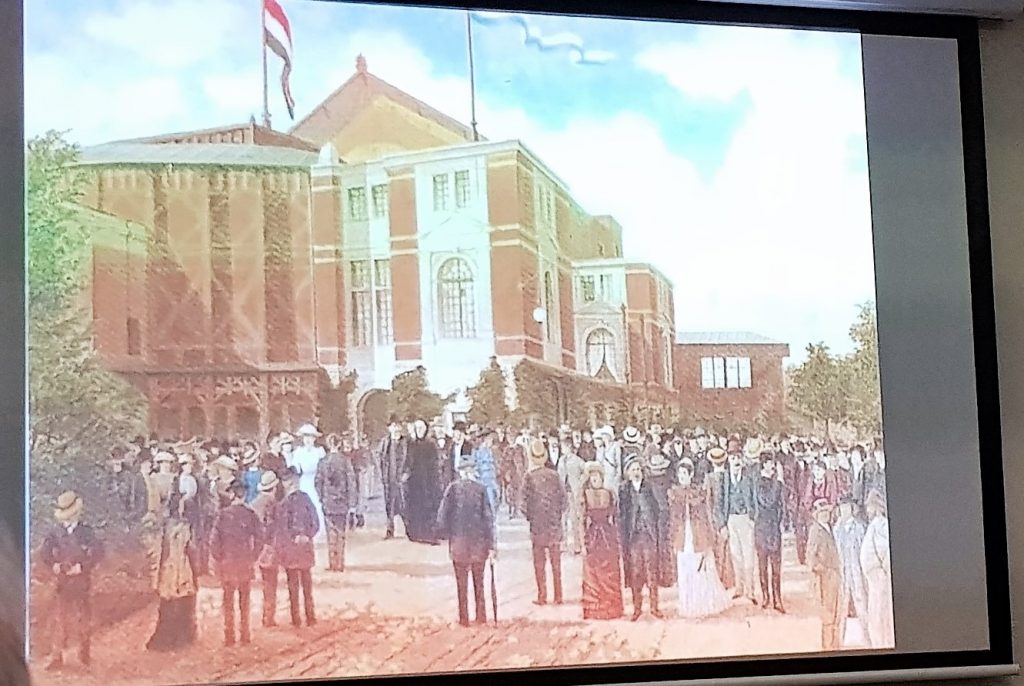

The Society’s September event of a private showing of Act I of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg followed by a Reception with French cake and Prosecco in the elegant Reception room of The Elizabeth Picture Theatre in Elizabeth Street Brisbane (the former Irish Club) was one of the most enjoyable functions of the Society.

The production was sponsored by one of our members, Richard Hartley, and a complementary eBook looking at the opera in depth was donated by Peter Bassett. The Glyndebourne production by Sir David McVicar was beautifully crafted to evoke a very naturalistic approach to the opera that highlighted the various characters and the period in which the action was set, despite the costumes being a couple of centuries later! The Prelude under the baton of Vladimir Jurowski was exciting, and the high standard of the singing of all the main characters was faultless. It was wonderful to see a production that was true to Wagner’s vision and not the vision of a modern director! Gerald Finley was a very balanced Hans Sachs, and I look forward to Acts 2 and 3 when Marco Jentzsch as Walther comes into his own as his character matures and allows his singing to exude more melodic power, while maintaining the connection to nature that makes his character stand apart from the very conservative approach of the guild members. Similarly, the following Acts will give greater scope to Anna Gabler as Eva, but this Act gave a true feeling of the actual Meistersingers and even made Sixtus Beckmesser a little more human!

This is the second time that a similar event has been held by the Society, and the comfort and exclusiveness of seeing a good production on the large screen is so enjoyable that we look forward to it becoming a yearly highlight.

Observations by Rosemary Cater-Smith.

Meeting photography by Cathie Duffy, Jennifer Lawrence and Judy Xavier

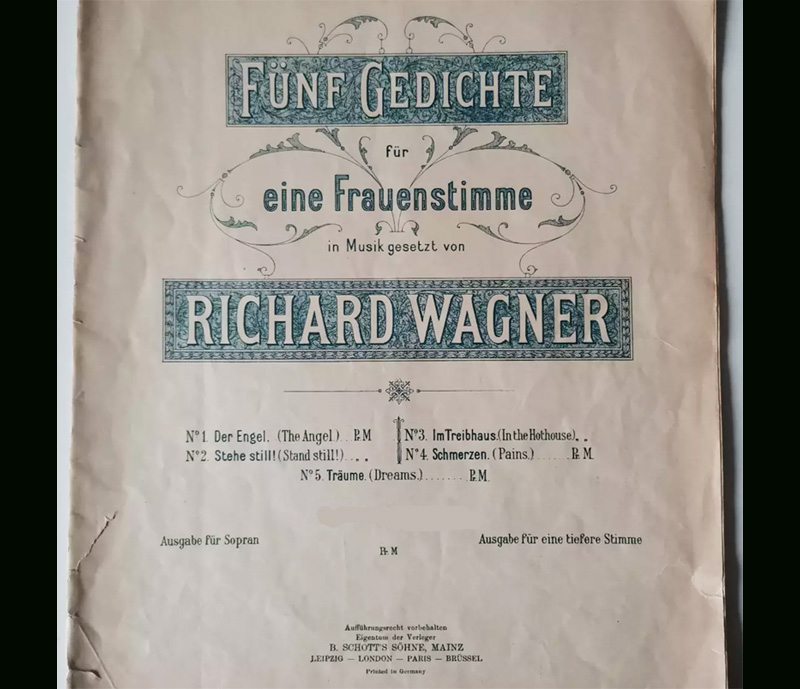

WESENDONCK LIEDER. INTRODUCTION BY STEPHEN EMMERSON FOLLOWED BY A RECITAL BY REBECCA CASSIDY WITH STEPHEN EMMERSON. Saturday 17th August 2024.

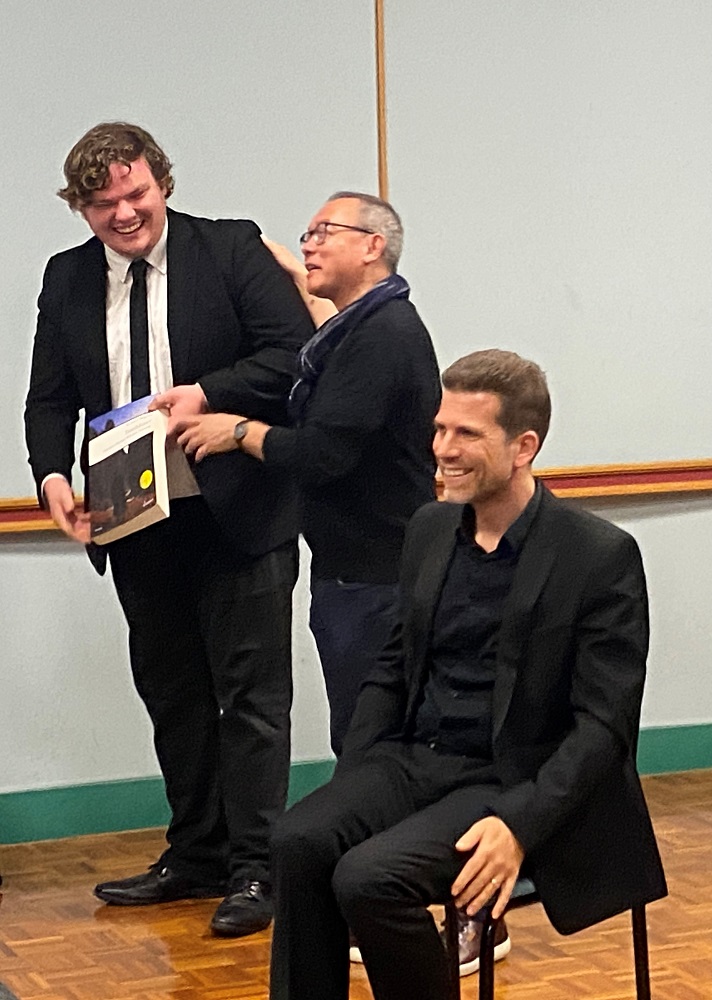

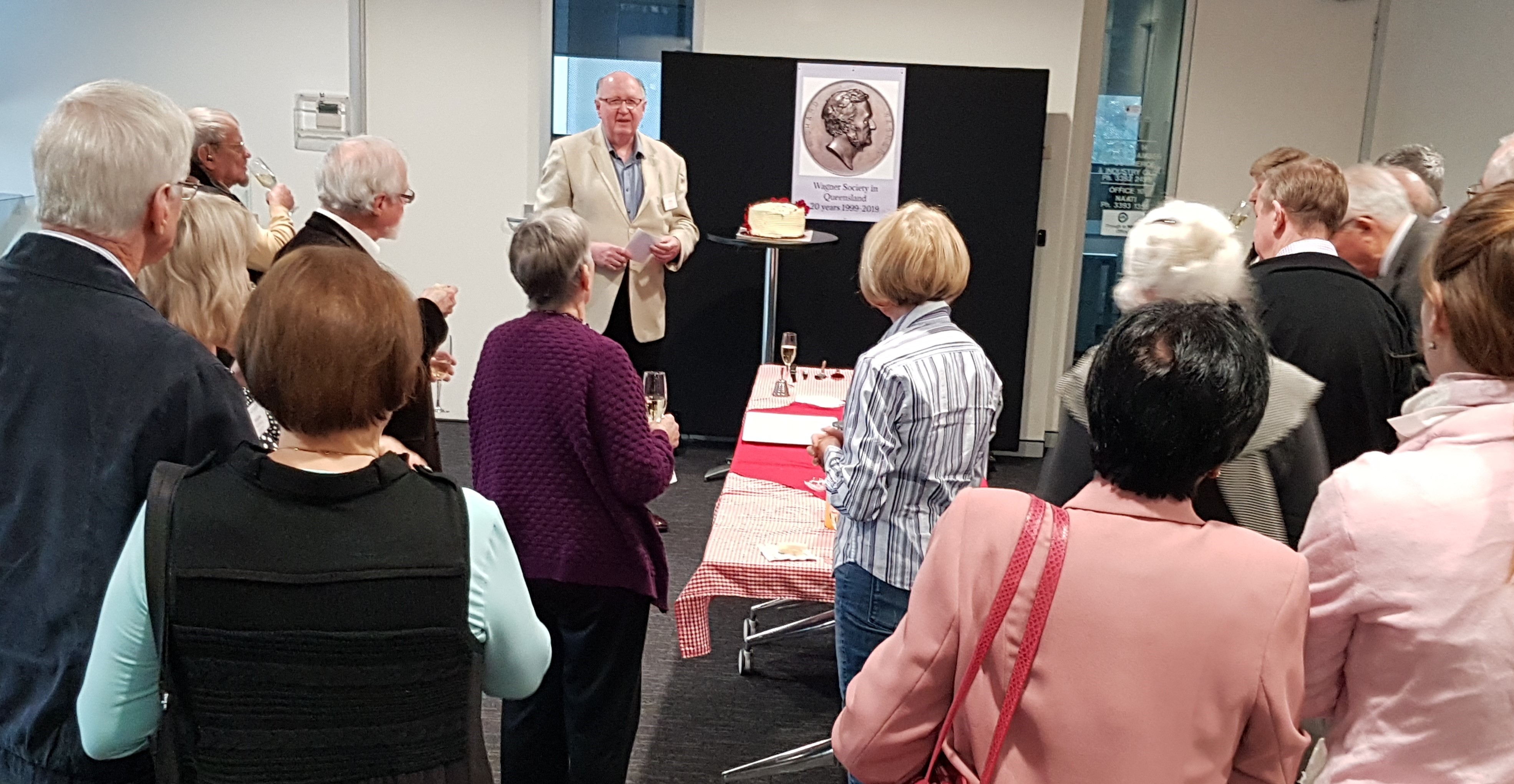

Saturday 17th August, 2024 was the 25th Anniversary of the founding of the Wagner Society in Qld. Following the performance of The Ring Cycle in Adelaide in 1998, a number of people got together with the intention of forming such a Society. Several informal meetings were held, and assistance was given by Peter Bassett who came to Brisbane from Adelaide. On 17th August 1999 a formal meeting was held appointing a Committee, of which Hal Davis was the first President. In 2024 six of those original members were present, as was Peter Bassett, and were presented with a bottle of Champagne to commemorate the event. A further bottle was raffled and won by one of the original members!

Stephen Emmerson gave a very enjoyable and most illuminating talk on the Wesendonck Lieder before a performance was given. He outlined the situation where Wagner and his wife Minna resided in a villa on the Wesendonck Estate, and Wagner’s relationship with Mathilde. It was a close spiritual relationship, but whether it was physical will never really be known. It was a very informative talk giving rise to a completely different assessment of Mathilde and showing her as a talented woman who spoke several languages and wrote poetry and plays.

A wonderful Concert of Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder was then performed by Rebecca Cassidy and Stephen Emmerson. Rebecca is a soprano with a wonderful talent, recognized some years ago by her winning of the Wagner prize given by the Society. She has gone from strength to strength, performing with the Qld. Symphony Orchestra, the Qld. Youth orchestra and the Opera at Jimbour event with Ensemble Q. In singing the Wesendonck Lieder her voice was powerful but rounded with a lovely tone and a soaring ability to reach the high notes with ease. Stephen Emmerson had full command of the piano and gave his usual accomplished performance, and together they gave a concert that made it a wonderful afternoon.

Members mingled to chat over afternoon tea, and a 25th Anniversary cake was enjoyed by all, accompanied, of course, with a glass of Champagne.

Observations by Rosemary Cater-Smith. Photography by Michael John, Jennifer Lawrence, Tom Elich, and Rosemary Cater-Smith

TONY PALMER’S FILM ON ‘WAGNER’. EXCERPT. Saturday 20th July 2024.

The Society meeting on 20th July had a slightly different format with a showing of part of the excellent film ‘Wagner’ starring Richard Burton. The film, produced by Tony Palmer, was originally seven and three-quarters hours in length, but had been reduced to a nine part mini-series. Stephen Emmerson did an excellent job in editing a section of the film that commenced with Wagner’s involvement in the 1848 Dresden uprising and concluded with King Ludwig II’s accession to the throne of Bavaria and his offer to support Wagner for the remainder of his life – an offer that was very welcome given the usual parlous state of Wagner’s finances! Richard Burton excelled in the role of Wagner, and Gemma Craven brought Minna to life as the wife who was unable to understand her husband’s genius and sought a more prosaic future for them both. The music was a highlight of the film, conducted by Georg Solti, and the scenery, shot on location was outstanding. With the supporting cast of outstanding actors, this is a film that has not dated given that its original production was in 1983, and one was left with the feeling that the mini-series in its entirety would be worth watching.

Observations by Rosemary Cater-Smith

RECITAL BY DALLAS TIPPET, RECIPIENT OF THE SOCIETY’S 2023 ENCOURAGEMENT AWARD, ACCOMPANIED BY MATTIAS LOWER. Saturday 15th June 2024

The Society was pleased to have as a recitalist at its June meeting the young baritone Dallas Tippet, winner of our 2023 Wagner Society Encouragement Award. This Award is offered on an annual basis, and those eligible are current tertiary students who, through performance in a major or minor role in a Conservatorium Opera production, best demonstrate vocal potential for a future career in large scale romantic operas in the style of Richard Wagner or Richard Strauss. The adjudicators are Heads of the Vocal and Opera Departments and all producers of opera programs during the year, and the Award is determined during the end-of-year examination period. The Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University is responsible for the administration of the Award and the managing of associated funds. We welcomed the attendance at the June 15th meeting of Associate Professor Margaret Schindler, Head of Vocal Studies of the Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University.

Accompanied on the piano by his singing teacher, tenor Mattias Lower, Dallas performed 4 musical items:

Träume – from Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder

Mein Sehnen, mein Wähnen – from Korngold’s Die tote Stadt

Lieben, Hassen, Hoffen, Zagen – from Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos

O du, mein holder Abendstern – from Wagner’s Tannhäuser

Dallas possesses a high baritone voice of beauty and flexibility, used to telling effect in meeting the challenges of technique and interpretation posed by the above musical items. The programme also included a discussion session, chaired by our Secretary Alpha Yap, when Dallas and teacher Mattias talked of Dallas’s development as an artist and his future career possibilities.

Though initially attracted to music theatre and jazz in high school, Dallas was persuaded by Mattias to give classical a go and ever since he has embraced with enthusiasm opera, art song and performance of other classical vocal music. While there are some vocal similarities to jazz, classical music demands more physically and emotionally and is for Dallas much more satisfying.

Dallas has undertaken his classical training at Queensland Conservatorium of Music, having completed his Bachelor of Music (Performance) at the end of 2022. He has just recently completed his Graduate Certificate and plans to finish his Master’s course in the middle of 2025.

Mattias has remained Dallas’s singing teacher for over 7 years. Their teacher/student relationship has been founded on mutual trust and a secure understanding of one another personally and artistically. During that time Dallas’s voice has developed from bass baritone to high baritone. In regard to the demands of performing classical repertoire, Dallas observed that movement classes at the Conservatorium aided stamina but that the singer must have mental resilience, must want to perform. Interpretatively, he felt that singers must find emotions from within themselves in response to the music rather than being too analytical.

Asked about repertoire progression and where his voice might go, Dallas was uncertain as to the ultimate destination. At this stage he is particularly interested in Mozart, Handel and Lieder, but he will continue to expand his repertoire in the high baritone range generally. Dallas added that he enjoyed English folk song, especially the songs of John Ireland. He agreed with Mattias that his voice could be suited to the lyric baritone roles of the Verdi operas.

After completing his Masters, Dallas hopes to engage in performance and further studies overseas. He intends to audition for a conservatorium in Germany or possibly the Royal Academy of Music in England. He will take every opportunity that may arise.

We wish Dallas every success as he works to develop his career as a classical singer.

Observations by Geoff Fisher

Photography by Cathie Duffy

WAGNER’S BIRTHDAY LUNCH, AND A PRESENTATION ON ‘RICHARD WAGNER AND THE TEPLITZ MYSTERY’ By Peter Bassett, Saturday 18th May 2024

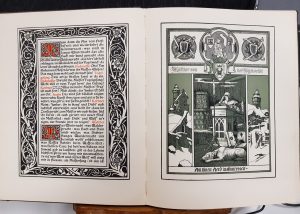

A map showing the likely route taken by Johanna Rosine Wagner when she travelled by coach from Leipzig to Teplitz in July 1813.

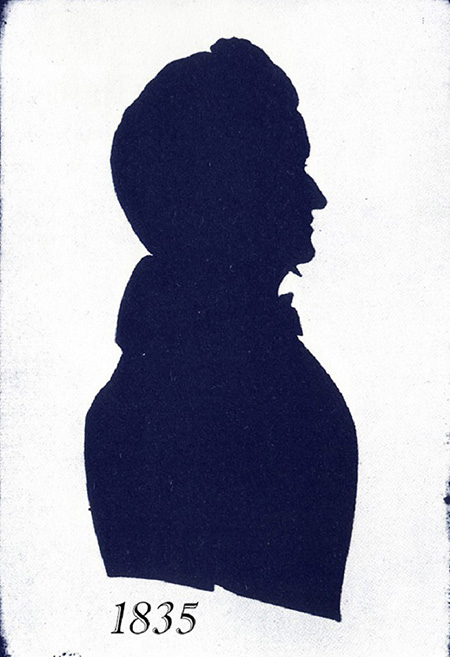

Left: Coat of Arms devised by Richard Wagner for the first printing of ‘Mein Leben’, combining a vulture (Geier/Geyer) representing Ludwig Geyer, and a constellation (Grosser Wagen) representing Carl Friedrich Wagner. Right: the heraldic eagle used by Napoleon I. Richard Wagner abandoned his coat of arms out of concern that the vulture might be mistaken for Napoleon’s eagle, with implications of ongoing Wagnerian sympathy for Napoleonic France. Richard specifically identified his father as “Carl Friedrich Wagner [1770-1813] at the time of my birth the Registrar of Police in Leipzig, with the expectation of becoming Director of Police”. He dismissed suggestions that his biological father was Ludwig Heinrich Christian Geyer, his mother’s second husband, and such claims (often repeated during the twentieth century) are based on unfounded speculation. Saxony was an ally of Napoleonic France until late 1813, and Friedrich Wagner had the confidence of the French authorities (Napoleon’s Marshal Davout appointed him Chief of the Police of Public Safety and asked him to act as an interpreter during Napoleon’s visit to Leipzig in 1813). This close association with the French must have become an embarrassment to later generations of the Wagner family and could explain the absence of any surviving portrait of Friedrich Wagner and Richard’s efforts during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 to distance himself from the French.

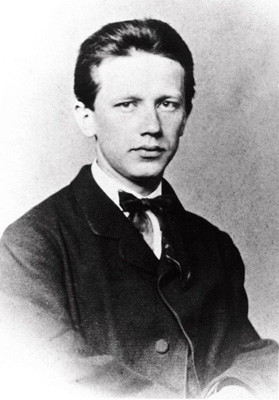

Left: Albert Wagner, Richard’s elder brother by fourteen years. Right: Richard Wagner as a young man. The clear physical resemblances between the brothers Albert and Richard provide persuasive evidence of the common paternity of Carl Friedrich Wagner.

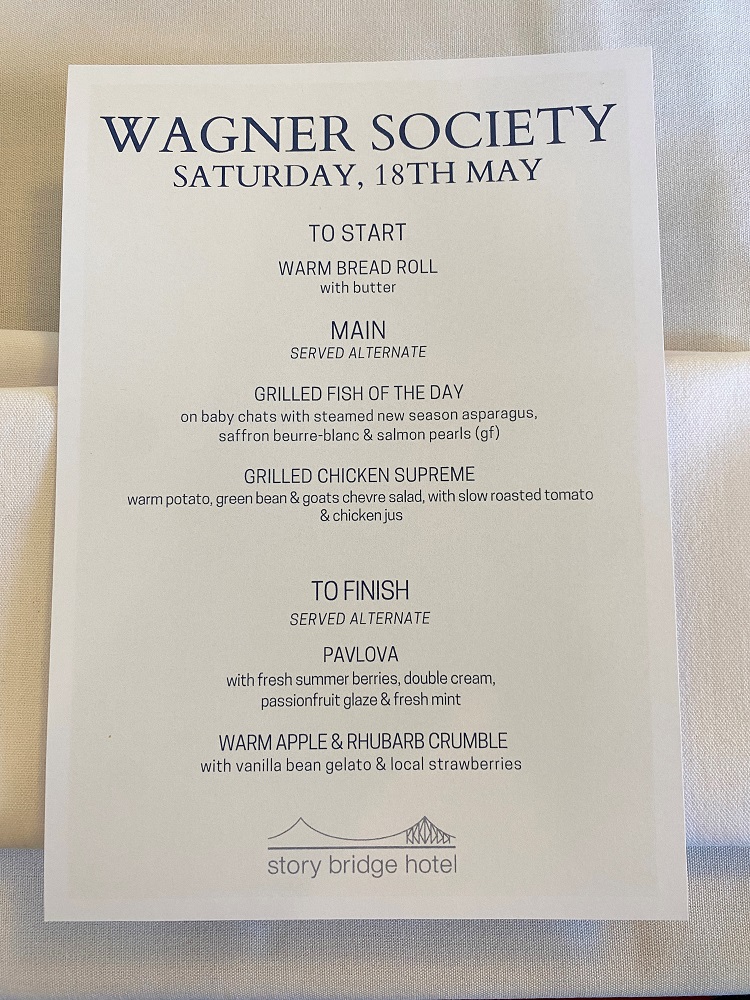

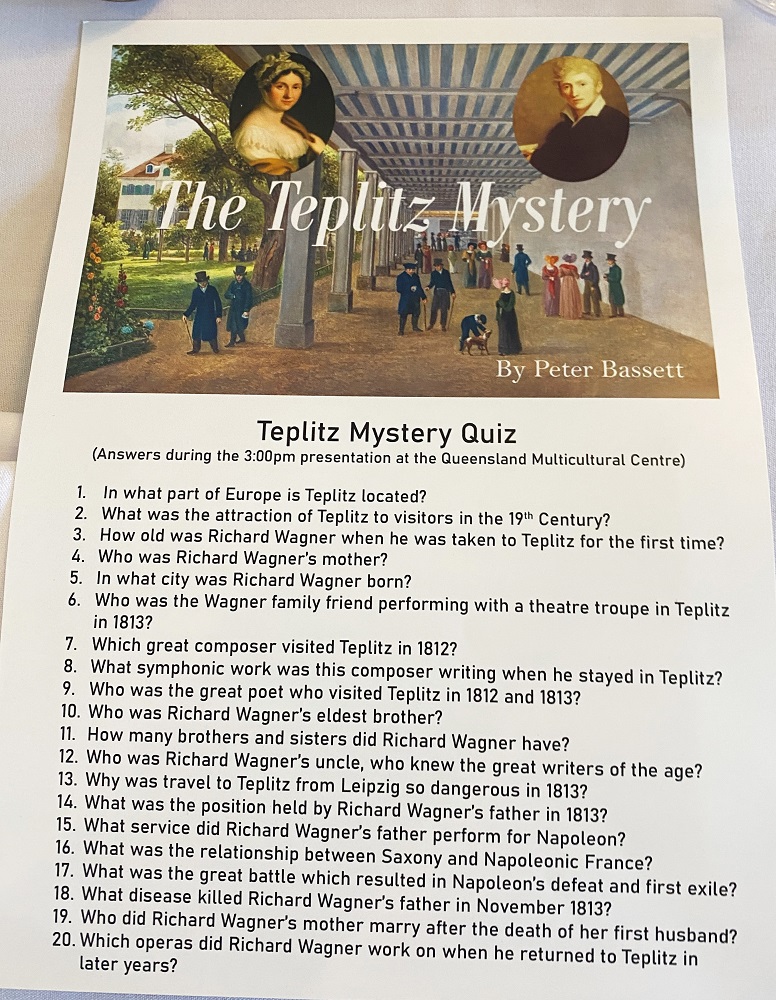

The Society’s annual lunch in commemoration of Wagner’s birthday was held on Saturday 18th May in the Heritage Room at The Story Bridge Hotel. Attendance numbers for both the lunch and the meeting to follow were very healthy, and our members and guests began with refreshments and a fine lunch amid delightful company. At each table we were faced with a sheet listing a range of questions – The Teplitz Mystery Quiz. Even for committed Wagnerians, I dare say that many if not all of the answers were unknown at the start of the afternoon. I guess that even “In what part of Europe is Teplitz located?” was a little hazy for many, including myself. “Who was the Wagner family friend performing in the theatre troupe in Teplitz in 1813”; “Which great composer visited Teplitz in 1812”; “Who was the great poet who visited Teplitz in 1812 and 1813; “Why was travel to Teplitz from Leipzig so dangerous in 1813”, and “What service did Richard Wagner’s father perform for Napoleon?” – these were just a few of the 20 intriguing questions posed.

After ambling back down to the Multicultural Centre after lunch, we were treated to a presentation by our former president Peter Bassett. Answers to all the Quiz questions were revealed and discussed in fascinating detail. The crux of the issue concerned the question of why Wagner’s mother Johanna risked undertaking travel from Leipzig to Teplitz to visit the family friend, the actor Ludwig Geyer. Amid the backdrop of the Napoleonic wars and at a time when country roads were notoriously unsafe, the trip seems ill-advised especially travelling with her young son Richard, then only a couple of months old. Wagner’s father would die later in the year, and his mother would before long marry Geyer. There has been much conjecture, together with more-or-less-subtle innuendo, that Richard Wagner’s biological father may not have been Johanna’s husband but in fact Geyer, and that Wagner’s mother risked taking the child to Teplitz to introduce him to his real father. Cause for such speculation can be traced back to statements by the composer himself as reported by Cosima and Nietzsche, and rumours have been spread widely by various subsequent authors. Some have also suggested that Geyer was of Jewish heritage – innuendo irresistible for some in light of Wagner’s later infamous antisemitism. (He wasn’t!) Many of us had probably heard such rumours so Peter’s setting the record straight on these issues was most welcome.

As we have witnessed many times, Peter’s presentations are always impeccably researched, clearly and persuasively argued. This was no exception. And the argument was supported by well-chosen projected images from the time and presented with his usual alacrity and gentle humour. His grasp of both the personal family dimensions as well as the broader historical context was masterly in its detail. Based on various forms of evidence, he built an argument – thoroughly convincing to this writer – that countered the speculations about Wagner’s biological father. Most persuasive were the images showing Wagner’s unmistakable physical likeness to an older brother, born long before his mother knew Geyer.

Another matter of particular interest was Wagner’s father’s relationship to Napoleon. As a senior public servant in Leipzig, Saxony (where Napoleon had appointed a sympathetic king), Friedrich was perceived to be acting on the side of the French leader – an association that accounts for why much information about him around these years was subsequently buried. The French were defeated at the decisive Battle of Leipzig later in that year of Wagner’s birth – the so-called Battle of the Nations, the largest battle before the First World War, involving around half a million men resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths and casualties. Personal motivations and decisions can be easily misunderstood, distorted, and misrepresented by proximity to such seismic events and Peter unpacked the many interconnected threads with consummate skill.

All in all, it was a most informative presentation, rigorous in its detail but compelling in its conclusions and a pleasure to witness. The Queensland Society is fortunate indeed to have such expertise in our midst.

Observations by Stephen Emmerson

Event photography: Cathie Duffy, Judy Xavier and Michael John

The Late Music Dramas of Richard Wagner: Philosophy and Music. By Colin Mackerras, Saturday 20th April 2024

On Saturday 20th April, Colin Mackerras gave a very interesting and stimulating talk on the late music dramas of Richard Wagner – Philosophy and Music. He referred to Schopenhauer as the main philosophical influence on Wagner, and outlined four main areas for consideration, namely compassion, women, the environment, and nationalism, all of which feature in the later music dramas.

Schopenhauer thought that compassion was the basis of morality, and this is seen in particular in Parsifal when Parsifal kills the swan and Gurnemanz takes him to task for his action. Schopenhauer did not extend his feelings of compassion towards women, something emphasized by Colin, and in this aspect Wagner clearly parted ways in that the women in his later works were strong women, Brünnhilde being, in Colin’s view, the real hero of the Ring, and Kundry also showing strength through fortitude. It was Isolde, however, who showed that music had roots in sexual consciousness in the Transfiguration.

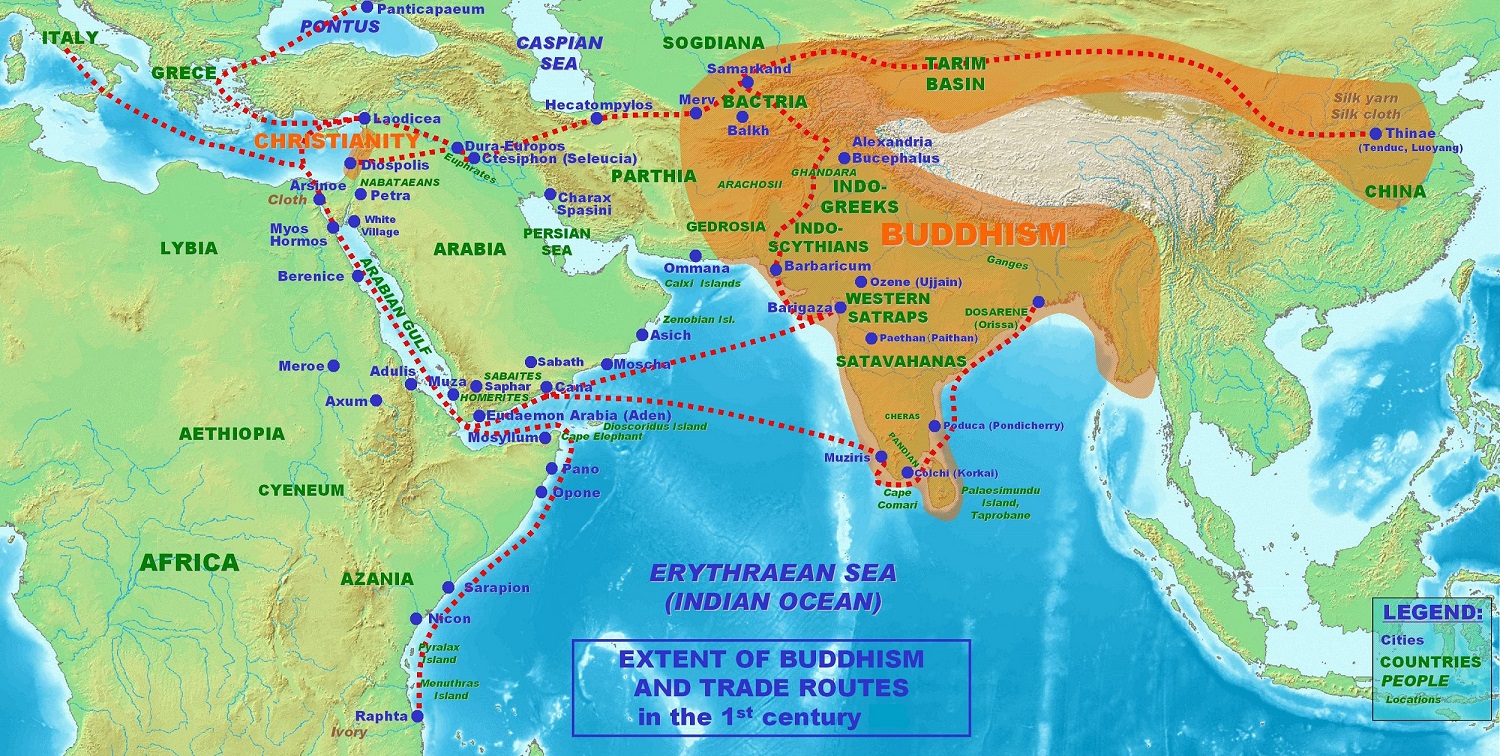

Wagner’s identification with nature is also seen in the Ring, particularly the Forest Murmurs in Siegfried, and his nationalism is readily apparent in his anti-French stance in the Franco-Prussian war. However, although Wagner’s works encompass and are influenced by these philosophical trends, his music embodies the concept of music as primary among the arts, a view influenced by Buddhism.

This primary position of music in Colin’s view was beautifully demonstrated in the Siegfried Idyll which dissolved the boundaries between Will and Representation, the dichotomy espoused by Schopenhauer. Altogether this was a provoking presentation and a highly enjoyable afternoon.

Observations by Rosemary Cater-Smith

Photography by Cathie Duffy

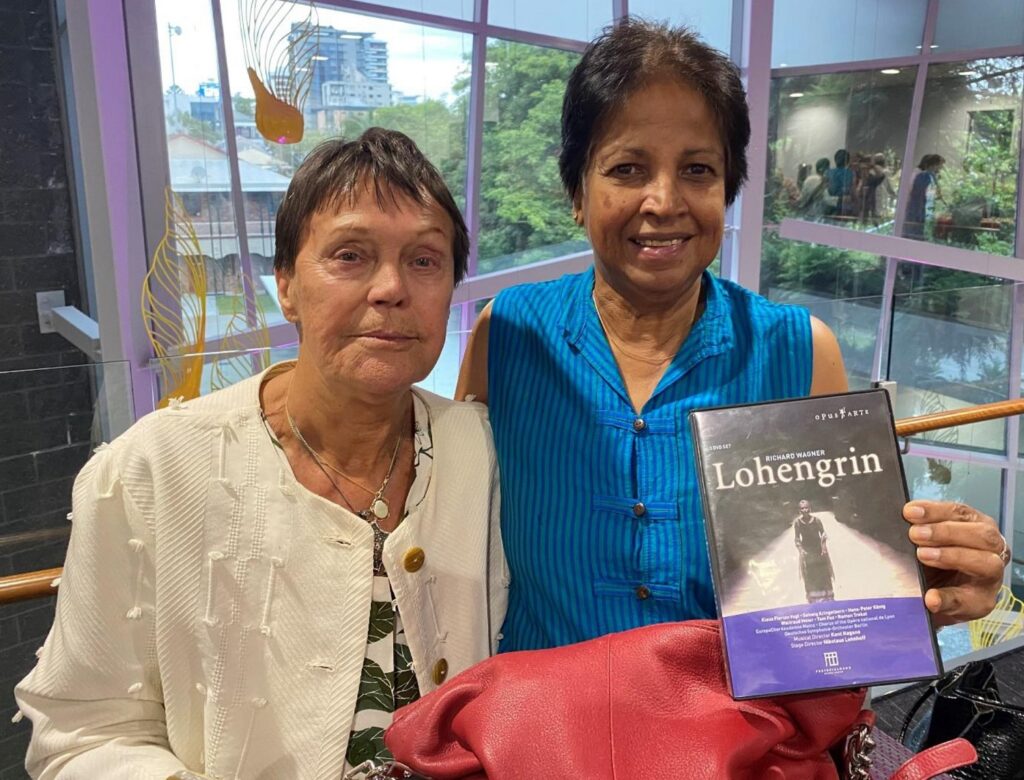

ACT 2 OF LOHENGRIN DVD. Introduced by Stephen Emmerson, Saturday 16th March 2024

Photography by Cathie Duffy

ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AND ‘AFTERSONG’. Saturday 17 February 2024.

Our first meeting for 2024 was held at the Story Bridge Hotel, and combined the 2023 AGM (delayed because of the many commitments associated with the Brisbane Ring) followed by Aftersong, a series of reflections on the Brisbane Ring. A key function of the AGM was to elect a new Management Committee for 2024. All of the members of the outgoing Committee were nominated for and elected to the new Committee, along with two new members: Michael John and Marion Pender. A complete list of the 2024 Management Committee is to be found on the Home Page of this website.

We had the pleasure of welcoming the Society’s Patron, Bradley Daley, for Aftersong. Bradley gave us many insights into the process of creating a new production on such a scale, taken with his experience with other recent Rings, including the Longborough and the Bendigo (Melbourne Opera) productions. Producers and production staff sought advice from experienced performers like Bradley, in a spirit of collaboration. And it was striking to learn how much was created or modified during the workshopping of the production (which was substantially done at Opera Australia’s home in Sydney, before being set up in Brisbane for technical rehearsals). We discovered much about the performers’ challenges. The digital screens that were so visually striking for the audience didn’t give as much support to project the voices as conventionally built sets. And lyrical soft passages in the orchestra can be a nightmare for singer trying to hear their cues. It was a charming insight into the depth of craft and skill that performers, technicians and producers, brought to create something on the scale of the Brisbane Ring.

Bradley’s Q and A session was followed by brief reflections from Society members (Colin Mackerras, Alpha Yap, Hal Davis, Marion Pender, and Michael John). These ranged widely, touching on comparisons with other Ring productions, telling performances in Brisbane, how the venue enhances the experience, and the immersive drama of experiencing a work of this scale as a living thing in the theatre. And Marion Pender had perhaps the best line of all: How wonderful it was to go home to one’s own bed after each performance (i.e. not be jetlagged!)

Andrew Porter, for many years The New Yorker’s music critic, once wrote of how the rhythms of life can change when one attends a Ring. The events of the week revolve around the performances, and one’s imagination is carried across the days by the evolving drama. The reflections of Aftersong and the later discussions over afternoon tea suggest that this was exactly the experience for many of us who attended the 2023 Brisbane Ring.

Observations by Alpha Yap Photography by Cathie Duffy

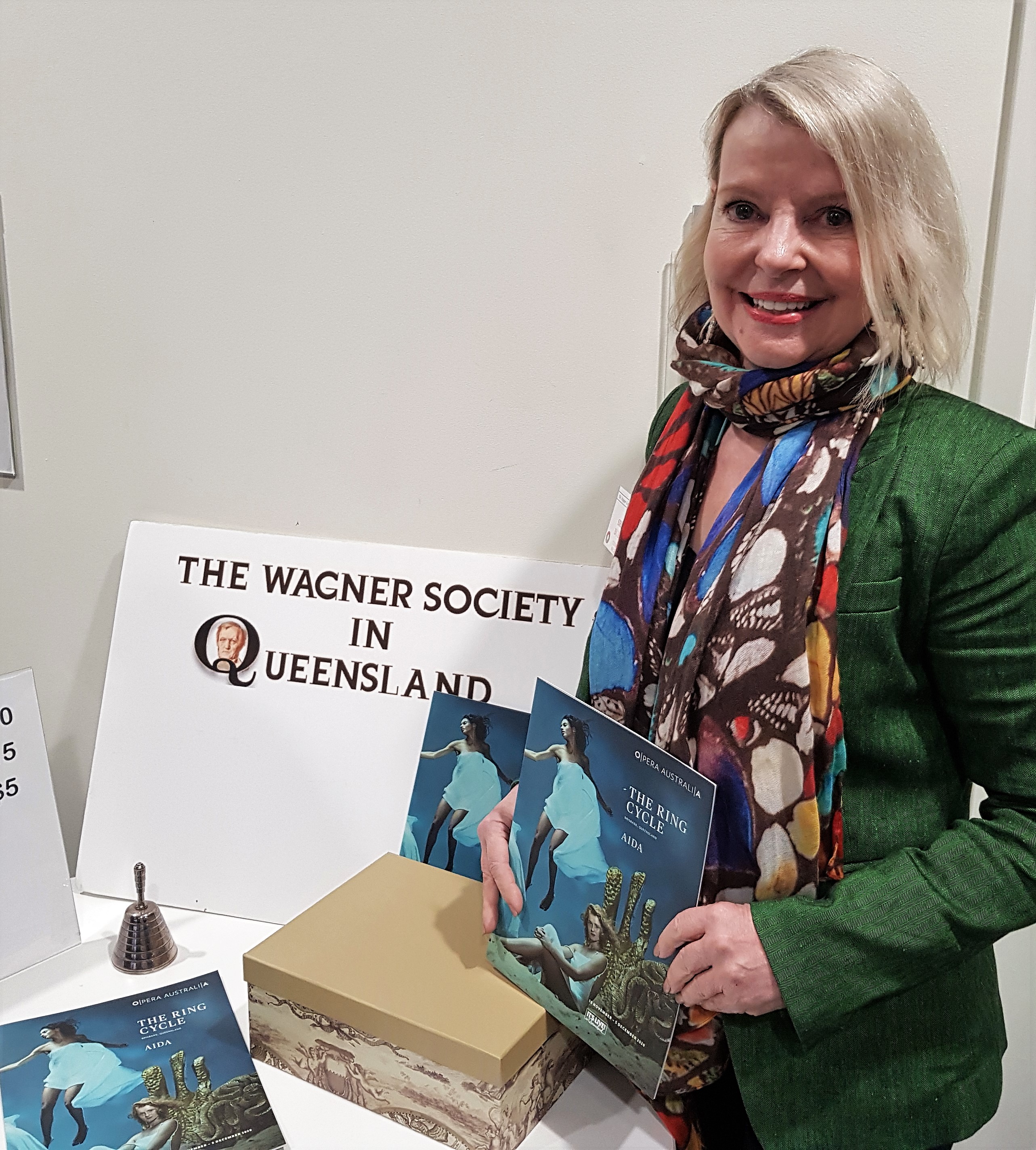

WSQ RECEPTIONS DURING THE BRISBANE RING. Saturdays 2, 9, 16 December 2023.

During the performances of The Ring Cycle in Brisbane in December 2023, the Wagner Society in Qld. arranged three Receptions to greet visiting Wagnerians. Each of these Receptions was held in conjunction with one of the cycles, and it was a great pleasure to welcome over 240 people from both National and International Societies. An outstanding attendance was approximately 45 members from New Zealand attending the second cycle. The venue for the Receptions was Tattersall’s Club, Brisbane, a beautiful Club that describes itself as the connection between Brisbane’s rich heritage and its progressive future. The lovely, elegant rooms provided the perfect background to the gathering that included the Presidents of several national societies, Esteban Insausti from N.S.W., Miki Oikawa from Victoria, Dr Geoffrey Seidel from South Australia and Alison Woodman from Western Australia. Our President welcomed all those present and acknowledged the considerable distance that some people had come to attend the Ring, including Wagnerians from New York, Frankfurt and Chile.

Prof. Dr Michael Rosemann, Honorary Consul of the Federal Republic of Germany in Brisbane highlighted the contribution made by German migrants who settled in Brisbane in a lively and stimulating presentation. Another highlight of the evenings was the playing by John Granger Fisher of the Liszt transcription of Wagner’s Liebestod, and we were delighted at the second Reception that our Patron, Heldentenor Bradley Daley, accompanied by John, sang Nothung. His attendance and singing was a wonderful addition to the evening.

It would not, of course, have been possible to hold these very enjoyable functions without the help of our sponsors. One of the first to make a significant contribution was Philip Bacon of Philip Bacon Galleries. Dr Philip Bacon AM is an art dealer and philanthropist well-known for his contribution to the arts in Australia. This was followed by a contribution from The Sydney Savage Club, known for its support of musicians. However, much support came from several of our own members who made very generous donations, and to members who participated in the other fund-raising activities organised by the Society.

Brisbane must now be considered a major arts venue having hosted a significant and highly enjoyable Ring Cycle, Symposia and Pre-Performance Talks by our immediate past President, Wagnerian scholar Dr Peter Bassett, and the wonderful and warm Receptions that brought all of us together.

Observations by Rosemary Cater-Smith, President

Photography by Cathie Duffy

BARITONE WARWICK FYFE – ALBERICH IN THE FORTHCOMING RING. Warwick and his wife Ruth were welcome guests during Ring rehearsals. Saturday 18 November 2023.

The Society was fortunate to have as its guest at the November meeting Warwick Fyfe, one of Australia’s most highly respected bass baritones. Warwick has built an impressive Australian and international career performing in challenging and complex roles, particularly in the Wagnerian repertoire. Warwick’s talk to the Society was especially timely in view of his forthcoming assumption of the role of Alberich in the Ring in Brisbane this December.

Warwick began by providing a candid and thoughtful overview of how his career in opera has developed from his early days at the Victorian Conservatorium to now performing in the great opera houses of the world. The professional life of a performer of classical music is at the best of times a demanding one. As well as the normal career hurdles, Warwick recounted his problems with ill-health and the vicissitudes of working at a time of Covid disruptions.

From an early age Warwick had immersed himself in Wagner’s works and in much commentary and analysis of them. But he realised that he should study more widely to become a complete opera singer over a range of repertoire. And he cautions about becoming an “opera bore”. Warwick considers that the best singers, who can penetrate the depths of a role, are those who have wide cultural interests in literature, history, art and the like.

After these observations, Warwick engaged in conversation with Peter Bassett, who first met him in 1998 when he sang Fasolt in the Adelaide/Châtelet Ring. Peter raised various matters regarding interpretation of and preparation for roles in opera. For Warwick, the vocal/musical preparation and dramatic interpretation or characterisation are aspects of the same process. With his wide background in Wagner, he does not find the need to engage in abstract analysis or theorising when assuming a role in a Wagnerian opera. His interpretative decisions emerge intuitively from his close engagement with the score. But one should always be open to fresh approaches and the insights of others. Singers can of course have different work methods in regard to the vocal preparation of a role. Warwick finds it more satisfying to start at the beginning of the score and to move carefully through to the end. By following the musical and dramatic development of the role, fresh interpretative insights may be yielded.

Turning to the Ring cycle in Brisbane, Warwick provided intriguing glimpses of what is in store, referring to matters of interpretation and presentation that have occupied the director (Chen Shi-Zheng) as he sought to realise the Wagnerian tetralogy as a “universal myth”. Questions from the floor revealed that members were looking forward to the Brisbane Ring with much anticipation.

At the conclusion of the meeting the consensus was that we had been both entertained and informed by a most engaging guest speaker.

Observations by Geoff Fisher

Meeting photography by Cathie Duffy and Colin Mackerras

TRAINING SINGERS FOR WAGNER. Associate Professor Margaret Schindler in conversation with Professor Lisa Gasteen AO, and a vocal performance by Kira Dooner accompanied by Sarka Budinska. Saturday 21 October 2023.

L to R: Kira Dooner, Lisa Gasteen, Rosemary Cater-Smith, Margaret Schindler, Sarka Budinska.

Members of the society were treated this month to a presentation from three excellent singers: Lisa Gasteen (who needs no introduction to members of any Wagner society), Margaret Schindler, Head of Vocal Studies at Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University and Kira Dooner, the winner of the Society’s 2022 Encouragement Award. So, between the perspectives of young person embarking on an operatic career and those of seasoned professionals, the presentation offered many fascinating insights into the nature of the profession and its many challenges. The afternoon began with a short engaging recital by Kira supported most ably by associate artist Sarka Budinska on piano. A delightful programme was presented including music by Gluck, Strauss, Brahms, Puccini and Dvorak. Kira’s excellent potential was abundantly clear – she has an attractive voice that is always at the service of the music, the words and character being portrayed. With secure technical control and a reliable command of languages, she is obviously being trained well but she also demonstrated abundant natural talent, temperament and communicative skills that will stand her in good stead.

Her performance was followed by an interview with Margaret Schindler where Kira shared some of her experiences of studying singing at Queensland Conservatorium with Lisa as well as her future aspirations. Her personality shone through describing herself as a “Drama Queen” who is most attracted to music that expresses strong emotions. It was clear that she fully inhabits the music/roles she sings. She is realistic about her career prospects giving sensible responses to questions about her short-, medium- and long-term goals. But with her musical talent, her personality and communicative skills, her prospects seem very strong.

Then Margaret interviewed Lisa about her career, specifically about the training she received. The training of an operatic voices is clearly a demanding and complex process that requires many years, indeed decades, of careful development and sensitive guidance. Moreover it entails a deep responsibility, of which Lisa and Margaret are well aware. Even for talented young singers who attain some early recognition, the opportunity to study overseas with renowned teachers, within esteemed institutions and in cities with rich operatic traditions is no guarantee of success. Only a very small proportion of hopeful young talents will attain the professional opportunities they dream of, let alone maintain a long and successful career. Lisa recounted gratefully how well her initial undergraduate studies in Queensland with Margaret Nickson set her up. Surprisingly, by contrast, the lessons she took with distinguished overseas teachers invariably “ended in tears”. She returned to Margaret Nickson to get herself and her voice back on track. It was gratifying to hear that, on returning to Brisbane after studies overseas, Margaret Nickson and John Matheson – Tahu Matheson’s father – both gave most generously and unstintingly of their time and experience. Ultimately they cemented the strong foundations from which her career could take off. Recognising the need here for young singers to access training of the highest level was the impetus for establishing the Lisa Gasteen National Opera Program that, for over a decade now, has done so much for aspiring young Australian and New Zealand singers.

The interview touched on many aspects such as the challenges of finding the right teacher, the right manager and the right country in which to study – not necessarily a big centre such as London or New York where a talent can easily get lost. (Scandinavia was strongly recommended above Italy!) Most tellingly, Lisa observed that one does not set out specifically to train a Wagnerian voice – any teacher claiming to do that should be avoided at all costs! For her, a teacher should develop the individual vocal instrument, build the muscles carefully over time for healthy, open sound production. Only down the track will the nature and potential of that individual’s instrument reveal itself. Careful choice of repertoire at each stage of this process is obviously crucial. For any young artist, singing Wagner – even the lighter roles – is necessarily some way down the track. The presentation was among the best attended of the year and lively conversation continued over afternoon tea.

Observations by Stephen Emmerson

Photography by Judy Xavier

Also see the Essays & Reviews page of this website for: Wagner’s plans for Training Singers, by Peter Bassett. A paper presented to the 8th International Congress of Voice Teachers, Brisbane, on 13 July 2013.

110 YEARS OF THE RING IN AUSTRALIA, by Dr Peter Bassett. Saturday 16 September 2023.

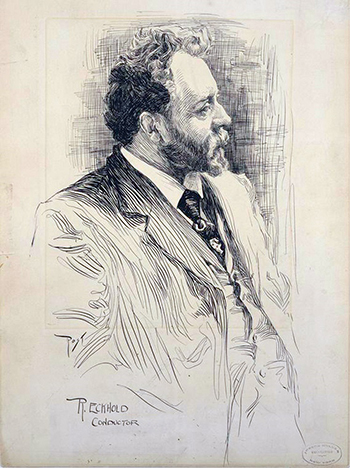

Thomas Quinlan, impresario 1912 and 1913.

Richard Eckhold, conductor of the 1913 Ring.

Maud Percival Allen 1913.

Florence Austral, star of the 1934 opera tour.

The 1998 Adelaide Ring.

Marilyn Zschau, Australian Opera 1989.

Froh, Adelaide Ring 2004.

The 2004 Adelaide Ring.

Lisa Gasteen, Adelaide Ring 2004.

Comparing Rhinemaidens. Armfield’s 2013 OA Ring above; Kosky’s 2009 Hannover Ring below.

Comparing Valkyries. Armfield’s 2013 OA Ring above; Zambello’s Washington DC/San Francisco Ring below.

Fasolt, Loge and Fafner, Melbourne Opera’s Ring 2023.

Our society members were treated to another excellent presentation on 16th September by our former president Peter Bassett. For some years we have been exceedingly fortunate to have such a committed, deeply knowledgeable Wagnerian in our midst who shares his passion and deep expertise so generously.

This presentation, titled 110 YEARS OF THE RING IN AUSTRALIA, outlined the fascinating history of Wagner’s music in this country, specifically through performances of his Ring cycle. Peter’s talk spanned from a Lohengrin performance in 1877 – we were even shown Wagner’s letter of appreciation for that production – through to Brisbane’s upcoming productions this year. Following the first staged performances of the Ring before the First World War, over 8 decades would pass before Australians could witness a production of the full cycle in this country. Astonishingly, a touring company directed by English entrepreneur Thomas Quinlan presented productions of virtually all of Wagner’s mature works in Melbourne and Sydney in 1913. (The only omission was Parsifal which was, at least up until that year, the exclusive preserve of Bayreuth.) In Melbourne, the company presented 25 different operas in eight weeks including two full Ring cycles as well as Aida that coincidentally will also be presented in the upcoming Brisbane season. And several Ring cycles were presented in Sydney together with some extra performances of Die Walküre and Götterdämmerung. Clearly after the world war(s) the many diverse challenges of producing a complete Ring cycle proved to be prohibitive for many subsequent decades. Benjamin Fuller in the 1930s brought productions of Wagner’s works (including around a dozen performances each of Die Walküre, Tristan and Tannhäuser among other operas). The star soprano of these performances was Australian soprano Florence Austral and we were treated to hear a recording of that remarkable voice from 1928 (in an extract from the Prologue of Götterdämmerung). Peter also drew our attention to another famous Australian Wagnerian soprano Marjorie Lawrence. Though she never performed a Wagnerian role here on stage, her concert performances were memorable events in the musical life of our country.

No productions of the Ring were seriously contemplated in Australia in the decades immediately after World War Two. Peter then described the attempts of Australian Opera to produce a Ring cycle in the late 1970’s that were thwarted by internal disputes and personal rivalries. A concert performance of Das Rheingold in Sydney in 1979 and Die Walküre two years later in Sydney seemed promising but Richard Bonynge’s intention of presenting a complete cycle that decade did not eventuate. A 1984 production of Das Rheingold was unfortunately decisive. Peter cited Moffatt Oxenbould’s opinion that it was “one of those performances one would like to forget, but never can, because the memories of a horribly bad performance remain so vivid.” As a result, from that point on, plans to complete the cycle were regrettably buried for over a decade.

And so South Australian Opera’s presentation in Adelaide of the Ring cycle in 1998 was the major turning point for Wagner performances in this country. Pierre Strosser’s 1998 production (imported from the Châtelet in Paris) was followed by our first fully-staged Parsifal in 2001 and the first Australian production of the Ring cycle in 2004. Many of us present will have recalled the exhilarating experience of these performances and it was a delight to be reminded of what these productions looked and sounded like. In particular, extracts from a documentary film on the 2004 performances reminded us of the hugely ambitious nature of the production directed by Elke Neidhardt, showed us conductor Asher Fisch at work preparing the orchestra (a band of over a hundred musicians that, from all accounts, excelled itself) and to hear again some of Lisa Gasteen’s glorious – dare one say incomparable? – Brünnhilde. Taken with a video of rehearsals of the 1998 production, it was a vivid reminder of the extraordinary dedication required to put on a Ring cycle: extraordinary singers supported by a musical staff whose work finishes when the curtain goes up; many months of rehearsal by the orchestra(s); and dedicated technical teams who tackle the challenge of making the productions work!

Beyond its notable place in Australia’s operatic history, the 2004 production should be recognised as an outstanding landmark in our broader cultural history and not just for Wagnerians. It is great to be informed that videos of that extraordinary production have become available to view online and that a new book of photographs from it will be available soon.

Disappointingly, plans to restage the 2004 Adelaide production elsewhere in Australia failed to materialise and it wasn’t until 2013 that Opera Australia presented a production of the Ring in Melbourne. Peter noted the interstate rivalries that were operating behind the scenes. I suspect that many of us shared his reservations about that particular production directed by Neil Armfield, noting that many of the directorial concepts were “a bit of a hotch potch” (and he demonstrated its unacknowledged debt to some previous productions). And so, now a decade later, hopes are high that the Ring in Brisbane this year will be more original, more coherent and more compelling.

The Ring presented by Melbourne Opera in Bendigo from this year was also considered – a commendable achievement to be sure but Peter expressed and justified his reservations about ‘fairy tale’ or ‘folk tale’ stagings of Wagner’s works.

Peter’s presentation concluded with an audio extract from Warwick Fyfe and Daniel Sumegi singing from the Alberich-Hagen scene in Götterdämmerung – two wonderful Australian Wagnerian voices who were featured decades ago in Adelaide Ring cycles but will be heard again this year in the Brisbane performances. The sense of anticipation is palpable – only not to hear these fine voices again but to experience first-hand what will hopefully be another landmark in Wagner performance in Australia. Our heightened expectation was only enhanced by Peter’s superb and deeply authoritative presentation that put the event into a broad historical perspective.

Observations by Stephen Emmerson

Meeting photography by Judy Xavier and Colin Mackerras

Tahu Matheson’s Conversation with Stephen Emmerson. Saturday 19 August 2023.

On 19 August, the Wagner Society in Queensland was given a special treat when Professor Stephen Emmerson, adjunct professor with the Queensland Conservatorium of Music, part of Griffith University, interviewed Tahu Matheson, Head of Music of Opera Australia.

I liked everything about this occasion. In particular, I liked the easy style of both Tahu and Stephen, expressed in the enthusiasm both clearly feel for their subject. Secondly, I liked the content and especially the attention given to Wagner’s Ring Cycle, part of the preparation for the performances later this year. Thirdly, I liked the piano performances Tahu gave us, illustrating the complex music of Das Rheingold, especially the last part of it. I thought I knew this music well, but am happy to concede that Tahu’s presentation taught me a good deal about the brilliant ways Wagner varied his main thematic material. Tahu also said it was clear from the music that, although Wotan and the gods thought they were enjoying triumph through their entry into Valhalla, in fact their success was hollow.

Tahu Matheson is unusually tall and has a commanding presence. But his style is relaxed and informal, as well as informative. He did a degree at the Queensland Conservatorium and lived for a time in Brisbane. So, in fact Stephen was among his teachers and his abiding respect was obvious during the interview, both in manner and content. Stephen began by observing that it was Parsifal that had first got Tahu into admiration and love of Wagner, its sublimity and the calm way in which tensions are resolved, at least relative to Tristan and Isolde or the Ring.

It was the Ring that dominated the discussion, with some references also to Tristan and Parsifal. Tahu emphasized the influence of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) on Wagner’s music. One of the main sources of Schopenhauer’s appeal to Wagner was his notion that the truth of the world should be seen not in scientific but in aesthetic terms, music being “a copy of the Will itself” and the greatest of the arts. Wagner developed his own theory of the arts, but the libretti of his later works show the influence of Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation. A concrete example is in the wonderful first scene of Act III of Siegfried between Wotan and Erda, one of the turning-points of the Ring. Wotan needs Erda’s advice on how to “stop a rolling wheel” (wie zu hemmen ein rollendes Rad), that of the gods’ downfall. When she makes it clear she can’t help, he responds: Um der Götter Ende grämt mich die Angst nicht, seit mein Wunsch es will (“The downfall of the gods does not grieve me, since my wish wills it”). Again, in Parsifal we see a very important example of Schopenhauer’s view that compassion is the basis of morality. Who will save the Grail and return the spear? It is “the pure fool who gains understanding through compassion” (durch Mittleid wissend, der reine Tor). Tahu emphasized this crucial passage, acknowledging also the influence of Buddhism, in which compassion is central (Schopenhauer is famous for his interest in Indian philosophy).

As we come out of COVID-19 and can enjoy afternoon tea together after our Wagner experiences, let’s have more shows like this!

Observations by Colin Mackerras

Photography by Judy Xavier

SCHOPENHAUER IN TRISTAN: Beyond a usual love duet. Saturday 17 June 2023.

Presentation by Professor Stephen Emmerson.

Stephen Emmerson

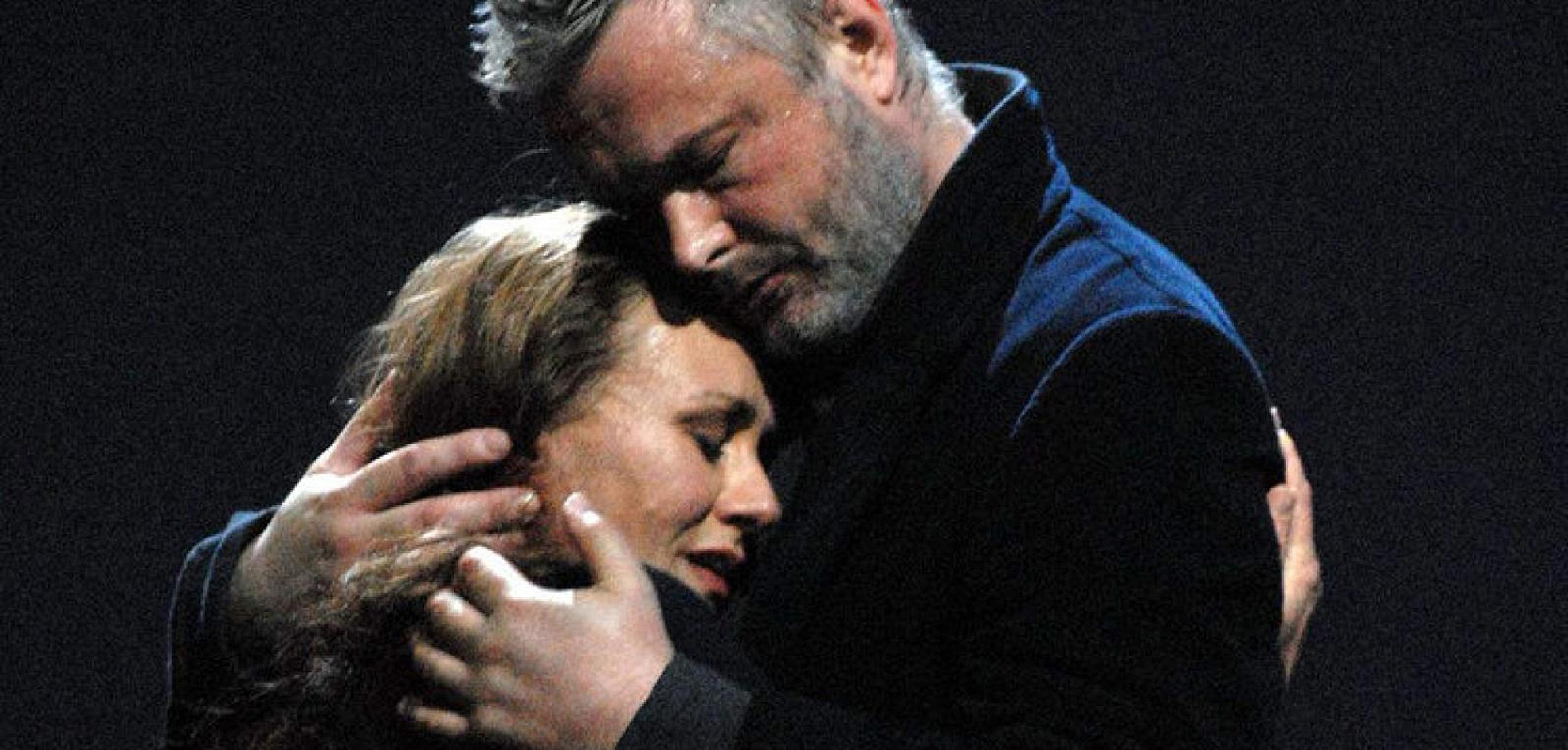

Ian Storey and Waltraud Meier as Tristan and Isolde

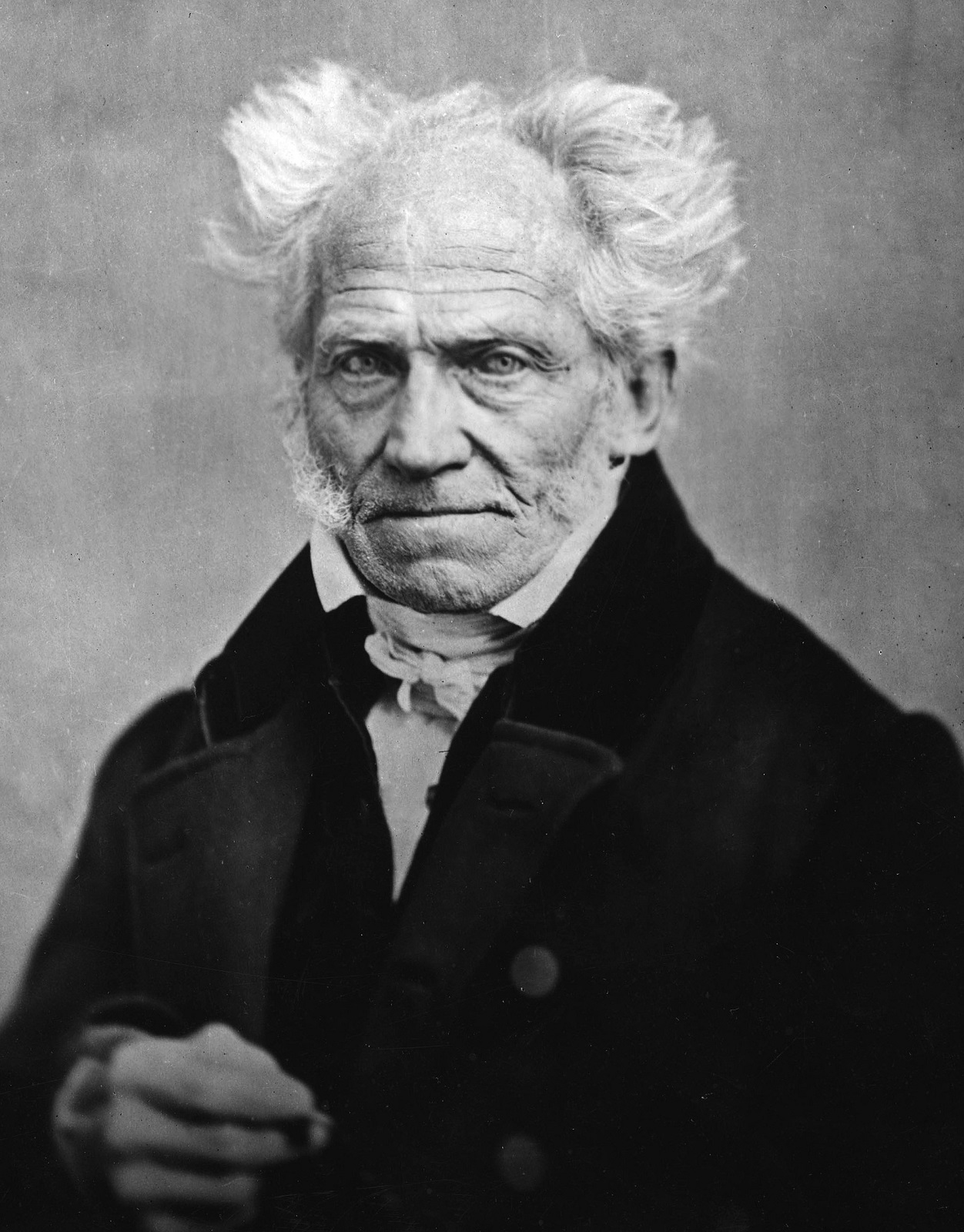

Arthur Schopenhauer photographed in 1859, the year in which Wagner completed Tristan und Isolde.

While modestly disavowing expertise in philosophy, Professor Stephen Emmerson nonetheless proceeded to give an informed and interesting presentation concerning the influence of the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) on Wagner and how this influence manifested itself in Tristan und Isolde.

Stephen focussed on the works of two distinguished and prolific modern philosophers: Bryan Magee (1930-2019) and Sir Roger Scruton (1944-2020). Some members of our Society would be acquainted with a few of the many books that these two polymaths and ardent Wagnerians wrote on a large variety of subjects.

Wagner first discovered Schopenhauer in 1854, working through his great treatise The World as Will and Representation (1818, expanded 1844 and 1859) four times in the course of the year. For Wagner this discovery was life changing. Till the end of his life Wagner stood in awe of Schopenhauer (as Stephen observed, Wagner was not exactly known for being in awe of any person). Schopenhauer’s influence pervades Tristan und Isolde, which Wagner composed in 1857-1859.

Schopenhauer, following Emmanuel Kant, drew a distinction between the phenomenal world of appearances and the noumenal world of absolute or true reality. According to Kant, the noumenal realm, ultimate knowledge of ourselves and the world outside us, is beyond the capacities of humanity to comprehend. Schopenhauer revised Kant by adopting a pessimistic view of our life in the phenomenal world while suggesting that humans might yet gain some access to the absolute. For Schopenhauer the world of appearances is illusory and characterised by suffering and frustrated desires. His pessimism is grounded in his concept of the ‘will’: a blind irrational force that animates all being in the universe. For humans this will manifests itself in continual wanting and striving which inevitably fail to satisfy. The way to overcome suffering, to achieve tranquillity of mind, is through the renunciation of the will.

Renunciation of the will can be achieved by ascetic self- abnegation and the submergence of individual identity, for absolute reality at its fundamental level is united and undifferentiated. All this has a close relationship to Hinduism and Buddhism, as Schopenhauer became happily aware when translations of Eastern religious texts appeared in Europe. But Schopenhauer did not believe in any afterlife and dismissed the possibility of reincarnation. Throughout Tristan, the lovers express their desire to merge their separate identities in the undifferentiated cosmos. They wish to escape the world of illusion, represented for them as the ‘day’, into the ‘night’ which is regarded as the realm of transcendence. Death might presumably seem to provide the only ultimate release from the sufferings of the world. But Schopenhauer did not advocate suicide, regarding it as an assertion of the will. Tristan and Isolde though express a longing for death as liberation from the realm of day: ‘Let us die and never part – united – nameless – endless – no more Tristan – no more Isolde…’

Not everyone is cut out to gain awareness of ultimate reality through asceticism or a mystical renunciation of the will. But as Magee recounts, Schopenhauer considered that people could see into the heart of things, if only momentarily, in two other ways: through sexual love and the arts, especially music.

Schopenhauer recognised that the most intimate knowledge of the human will to live is found in the ecstasy of sexual congress; however, the will to live is essentially selfish and the transports of sexual love cannot endure. Here Wagner departed from Schopenhauer, holding that sexual love may lead the will not only to some momentary self-awareness but to self-denial and transcendence. Tristan and Isolde sing: ‘O descend upon us night of love make me forget I live’.

Schopenhauer thought that the arts could reveal ‘the universal behind the particular, the universal through the particular’ (Magee). He privileged pure music as the most metaphysical of the arts, embodying abstract forms of feelings allowing for tranquil and transcendent states of mind. Responding to this Wagner moved away from his earlier ideas of Gesamtkunstwerk and the equivalence of the various arts in an opera. Stephen recounted that this resulted in Wagner now according primacy to music over the libretto, and in adopting a more symphonic conception along with more ensemble singing (duets/trios etc). This new approach is manifested in Tristan, particularly Act 2 which has been regarded as one long symphonic poem where the music drives the drama (Stein). But it must be cautioned that the words in Tristan cannot be disassociated from the music (Bassett).

Employing his musicological expertise, Stephen gave an insightful analysis of the structure of Act 2 of Tristan and the place within it of the extended love duet ( ‘O sink hernieder’) between Tristan and Isolde. The presentation concluded with a showing of the love duet from the La Scala production directed by Patrice Chereau and conducted by Daniel Barenboim, with the principal roles sung by Waltraud Meier and Ian Storey.

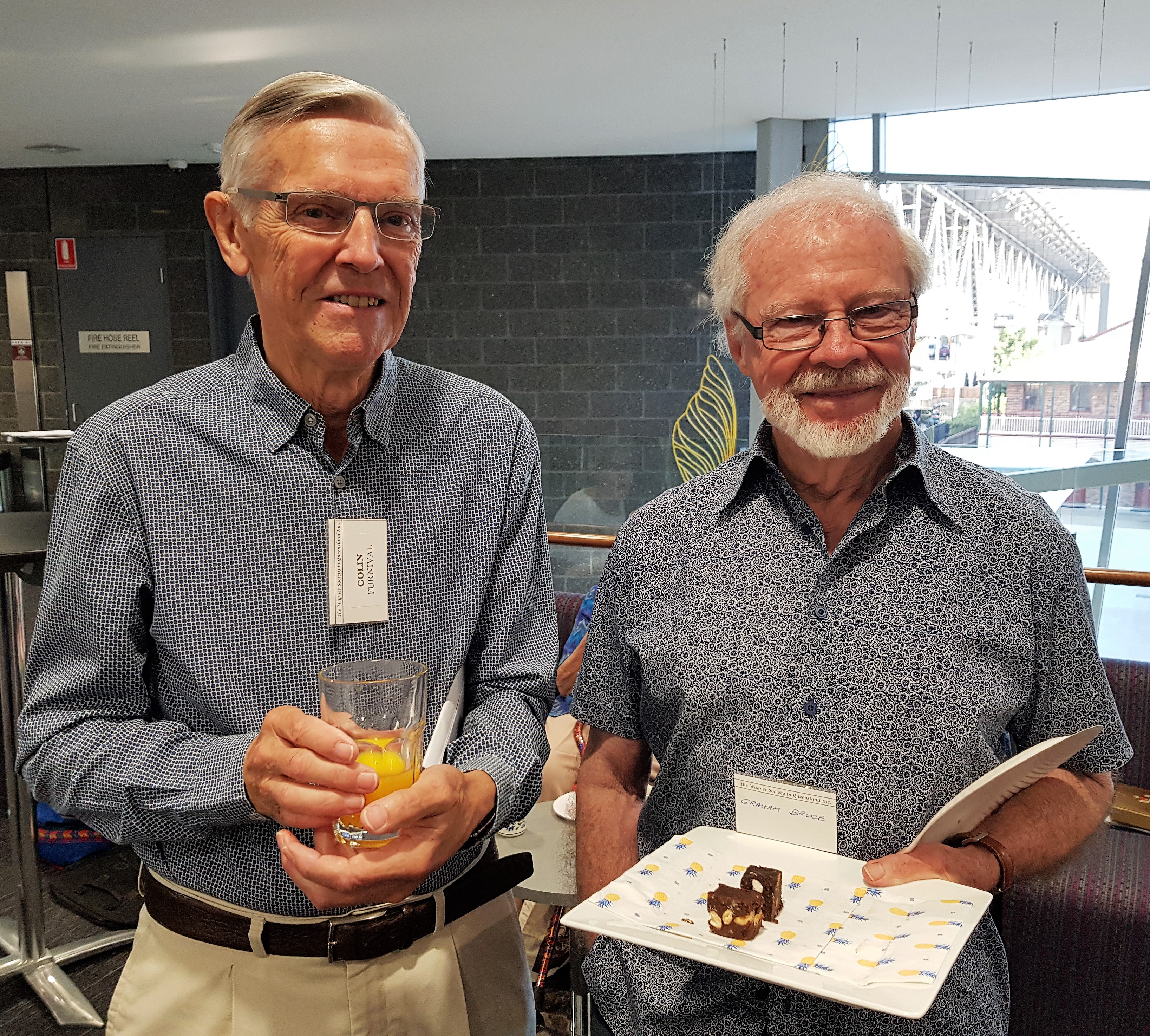

Prior to Stephen’s presentation, Colin Furnival spoke briefly about a production of the Ring he recently attended at the Staatsoper in Berlin. Another attendee of this production, Marion Pender, added some comments. Both speakers provided informative and interesting remarks. Conductor, orchestra and singers were of predictably high standard in the production. But the staging was a confusing and bizarre example of the Regietheater which has bedevilled Wagner’s operas.

Observations by Geoff Fisher

WAGNER BIRTHDAY LUNCH, STORY BRIDGE HOTEL. Saturday 20 May 2023.

Photography by Gidia Timmerman

PARSIFAL ACT III SCREENING FOR MEMBERS AND GUESTS, ELIZABETH PICTURE THEATRE. Saturday 15 April 2023

Brenda Beck and Tom Wohlmut, welcome guests from Santa Fe, a renowned centre for Wagnerian performances.

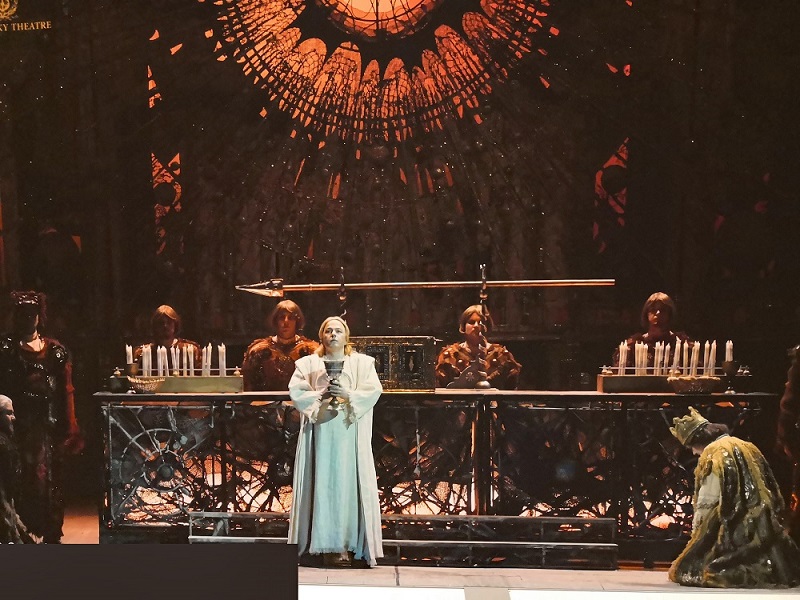

A different and highly enjoyable afternoon was held on Saturday the 15th April, with a showing of Act III of Parsifal followed by a Reception. The venue was the old Irish Club in Elizabeth Street which has now been converted to a very comfortable cinema, and the Reception rooms adjoining have retained the original charm and character of the building. The production of Parsifal chosen was that of the Metropolitan Opera in 2013, and the high quality sound made it quite a thrilling performance. What better to follow it than French cakes and Prosecco? Members are already asking for a repeat experience, and the Society is very grateful to the member who donated this wonderful afternoon. 52 members and their friends attended, and several visitors from overseas. It was a very good start to what promises to be an exciting year. Rosemary Cater-Smith, President

Cast and Production Team, New York, February 2013. Parsifal: Jonas Kaufmann. Gurnemanz: René Pape. Amfortas: Peter Mattei. Kundry: Katarina Dalayman. Klingsor: Evegny Nikitin. Titurel: Rúni Brattaberg. Conductor: Daniele Gatti. Production: François Girard. Designer: Michael Levine. Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus.

Peter Bassett’s Introduction to the screening of Parsifal Act III from the Metropolitan Opera.

Parsifal was Richard Wagner’s most deeply personal work, and it is a perfect example of how he constructed his mature dramas. He was drawn to myths and legends that lent themselves to musical treatment; and music, like myth, uses the language of feeling.

Musically, Tristan und Isolde and Parsifal have one thing in common – they use what has been called ‘sonic clusters’ from which musical strands are drawn and developed. This was a revolutionary approach in the mid-19th century, and it influenced many later composers. Wagner explained it this way: “Even before I set about writing a single line of the text or drafting a scene, I am already thoroughly immersed in the musical aura of my new creation.” It is useful to know that because it tells us that Parsifal is not just a story set to music – the music is the main vehicle for the story, and that can’t be ignored by stage directors.

In Tristan und Isolde, insatiable desire – a perpetual longing for things beyond our reach – can only be extinguished by entering “the wondrous realm of night” which lies outside a life of illusions and appearances as we know it – the world of day. But in Parsifal, there is another way to find inner peace – not through the portals of death but through compassion for the suffering of others. And “compassion”, said Schopenhauer, “is the basis of all morality”.

In 1857, Wagner and his first wife Minna had moved to the estate of Otto and Mathilde Wesendonck on the outskirts of Zürich, where they were given a cottage in the grounds. There, shortly after Easter, he was encouraged by the beauty and tranquillity of his surroundings to think of the Good Friday references in the old story of Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach. And, at once, he sketched out a drama in three acts that became Parsifal. So, work on Parsifal began while Wagner was in the midst of composing Tristan und Isolde. This is often forgotten because Parsifal wasn’t completed until 1882 and became his final work. The spirit that moved him on that spring day in 1857 was captured in the Good Friday scene in Act Three which we are about to watch. “Thus, all creation gives thanks for all that here blooms and soon fades, now that nature, absolved from sin, today gains its day of innocence.”

Traditionally, Good Friday was a day of miraculous happenings, and it seems to have been an especially propitious day in early literature. In Dante’s Divine Comedy, the poet set out on his spiritual journey on the vigil of Good Friday. In Wolfram’s Parzival, we read that on each Good Friday, a dove brought a wafer from heaven to lay upon the Grail and renew its powers. This is the origin of the final stage direction in Wagner’s Parsifal, according to which a white dove descends and hovers over Parsifal’s head.

The prelude to Act Three took western music into regions that were even stranger and more remote than those of Tristan. Today we can recognise in it a path to the music of Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg. It paints a desolate picture. Many years have passed, and the community of the Grail has been dispersed; the leaderless knights have been forced to forage for food like beasts. Gurnemanz emerges from his hut and encounters Kundry, now sleeping in the undergrowth. Gurnemanz is the elderly knight who had hoped that Parsifal would be able to save the stricken Grail community, but he had eventually abandoned him as just a foolish boy.

Kundry had been a tormented creature and a seductress, longing for sleep and death but condemned to endless rebirths. In the first Act, Gurnemanz had wondered whether she carried a burden of sin from a previous life, which is a curious remark for a Christian knight to make. In time though, we learn that in a former life she had laughed at the Saviour on the cross, which was the very antithesis of compassion. His own compassionate gaze fell on her, she says, and now she seeks him again “from world to world” – which is to say, from life to life.

At the end of Act Two, when Parsifal had rejected Kundry’s repeated attempts to seduce him, she was finally released from her suffering by the triumph of compassion over desire. The sorcerer Klingsor had told her: “He that rejects you will set you free”. Now it only remained for her to be reconciled with the Saviour through baptism.

A stranger approaches wearing black armour and carrying a spear. He sits wearily on a grassy mound and removes his helmet. Gurnemanz chastises him for being armed on such a holy day, but then recognises him as the boy who had killed the swan, the fool he’d driven away in anger. He also identifies the sacred spear and rejoices that he has lived to witness the day of its return. Parsifal remembers Gurnemanz and he learns that Amfortas, the Grail King, can no longer bear the pain of a wound once inflicted by the holy spear during his seduction by Kundry. He refuses to have anything to do with the Grail because of the agony it causes him, and the knights are in a pitiful state. The ancient Titurel, deprived of the Grail’s life-giving support, has died – a man like all men.

Parsifal laments his failure to do anything to prevent this misery. Realising that the youth must indeed be the one they have been waiting for, Gurnemanz helps him to a spring where Kundry bathes his feet. Gurnemanz scoops up some water and sprinkles it on Parsifal’s head. Kundry pours oil on his feet and dries them with her hair, and the old knight anoints him as the new Grail King. What is the point of all these details, so reminiscent of the Gospel accounts? Put simply, they illustrate Kundry’s path to reconciliation with the Saviour she had once mocked. That is what this scene is all about.

Parsifal’s first duty is to baptise the kneeling Kundry. He then remarks on the beauty of the meadow, contrasting it with the sorcerer Klingsor’s rank garden. Gurnemanz tells him that he is experiencing the magic of Good Friday, and we hear serene diatonic music that contrasts so wonderfully with the chromaticism of Klingsor’s sorcery in Act Two. Parsifal thinks that this should be a day of sadness, when all that blooms and breathes must weep. But Gurnemanz replies that this is not so. The tears of repentant sinners have sprinkled the meadow, and nature no longer sees the Saviour in agony on the cross, but man redeemed through God’s loving sacrifice.

In the distance is heard the sombre pealing of bells. It is midday, and Gurnemanz leads Parsifal and Kundry through the forest, through the rocky walls and into the hall of the Grail. This repeats the wonderful scene in Act One in which Parsifal says: “I scarcely tread and yet already seem to have come far.” To which Gurnemanz famously replies with Einsteinian prescience: “You see, my son, here space and time are one”. Einstein, by the way, was only three when Parsifal was first performed.

Two processions of knights enter, one bearing Titurel’s coffin and the other Amfortas on his litter. The two groups confront each other with mutual accusations in the centre of the hall at the covered shrine of the Grail. Now, the air is rent with the agony of a community utterly without hope. This is the music of pain, anger and despair, and it is one of the most dramatic scenes in Parsifal – indeed in all opera.

Titurel’s coffin is opened, and the knights break into cries of despair. They demand that now, for the last time, Amfortas must perform his duty and uncover the Grail. But he defies them, courting death and tearing open his bandages, imploring the knights to end his torment by plunging their swords into his body.

Meanwhile, unobserved, Parsifal has been watching these events. He steps into the midst of the knights, stretches out the holy spear and touches Amfortas’s side with its tip. The wound miraculously closes and Amfortas is healed. Compassion has achieved what nothing else could. Parsifal offers the Grail’s blessing to the worshipping knights and, high above, voices proclaim a heavenly benediction: Highest holy miracle! Redemption to the redeemer!

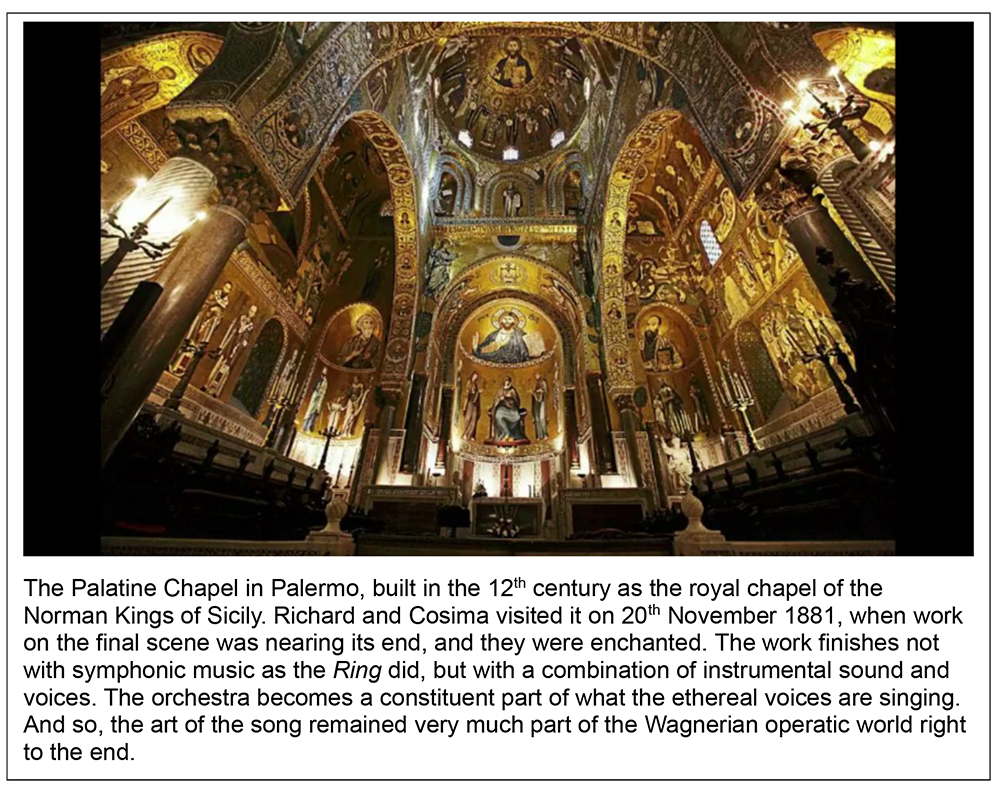

Wagner’s Parsifal was completed in Palermo, Sicily, on 13 January 1882, and its first performance took place in July that year at Bayreuth. Its impact on great composers who attended the earliest performances was overwhelming. Debussy described it as “one of the most beautiful monuments that has ever been erected to the eternal glory of music”. And Gustav Mahler said: “When I came out of the Festspielhaus, unable to speak a word, I knew that I had experienced supreme greatness and supreme suffering.”

And so, to Act Three from the Metropolitan Opera. This production was first staged ten years ago, in February 2013, and the video recording was made at that time. We are fortunate in being able to see it projected onto a large cinema screen and to hear the wonderful music in ideal circumstances. I add my sincere thanks to our generous benefactor who has made this possible, and has requested this introduction.

Stage productions can only proceed from limited perspectives – that’s the theatrical reality – and this 2013 production is no different. Here are a few comments by reviewers at the time. From David Allen in Bachtrack: “It is another in a long line of Wagner productions set in a post-apocalyptic world. …. In Girard’s telling, nature has been desecrated, and the steady, minimal staging grows with almost unbearably powerful images. … Girard, like Wagner himself, leaves questions unanswered – unlike the composer, he leaves too many.”

And from Robert Levine in Classics Today: “Despite Wagner’s instructions, the landscape consists of arid land and small mounds of earth. There is no forest or lake in Act One or springtime in Act Three, and neither the first nor third Act transformation scene offers any physical transformation. Gurnemanz and Parsifal stroll – the transformation is clearly inner…. Parsifal returns in Act Three utterly exhausted. He is not a knight in armour come to heal the world’s wound caused by the spear and, by association, by women; he doesn’t bring springtime and renewal. He simply comes back to do his job and to perform a ritual that for some reason brings comfort to a group of men and women. Some wounds have been healed, but the world outside is still barren. Kaufmann’s is a divinely beautiful performance …. but almost stealing the show is Peter Mattei as Amfortas, whose agony and self-hatred are terrifyingly real. The Met orchestra and chorus play and sing magnificently. You leave this performance wandering, like an imperfect fool, but fascinated.”

You can decide whether you agree with these observations made a decade ago. But, as I said at the beginning, Parsifal is not just a story set to music; the music is the main vehicle for the story, so please listen to it with that in mind. It is Wagner’s original creation that will survive, and Parsifal was, in many ways, his Credo and his farewell to the world. As Toscanini put it: “Every time I glance at the score of Parsifal, I say to myself: This is the sublime one.”

So, here is an intriguing modern perspective on Act Three from the Metropolitan Opera.

Peter Bassett.

Photography by Cathie Duffy.

POST-WAGNER GERMAN OPERA: WORLD WAR I BY PROFESSOR COLIN MACKERRAS. Saturday 18 March 2023

Professor Colin Mackerras was the speaker for our meeting on March 18th, 2023. He spoke about “Post-Wagner German Opera: World War I”. In a presentation lavishly illustrated with musical examples, Colin painted a vivid picture of the diverse directions that German opera took, despite the enormous historical weight of Wagner’s artistic legacy. He placed creativity during and after World War I within the context of the leadup to the end of empires throughout the world; the growth of nationalism and also human displacement both after the War and with the rise of Fascism in the 20s and 30s; and also the enormous artistic vitality and adventurousness in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

One implication of all this change was a loss of centrality of German art music, as had been epitomized by Wagner’s legacy at the end of the 19th century. How composers reacted was the theme of Colin’s talk, which he discussed by considering four examples.

Colin began with Hans Pfitzner’s Palestrina. Pfitzner was a superbly accomplished composer and conductor, and a major figure of musical conservatism in the first half of the century. Palestrina is often considered his masterpiece (by Thomas Mann and Bruno Walter, amongst others), highly valued still within Germany, but a work that has struggled to find a place in the repertory in non-German-speaking countries. Its story is the creation of Palestrina’s Mass for Pope Marcellus and, with it, the preservation of musical polyphony at a time when the Catholic Church was considering its prohibition (in favour of plain chant). To that extent, Palestrina upholds the power of individual artistic creativity in uncertain times.

Colin’s second example – Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos – was quite a contrast to this. Strauss’s third opera written jointly with librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Ariadne is an opera within an opera within a play: a lyrical Greek tale (with heroic soprano and tenor) mixed in with a comic troupe. Yet it is also a thing of its time: perhaps a reaction by the composer against the violence of his earlier operas (Salome and Elektra), but also a self-referential work (with a Composer as one of its characters) that mixes high drama with lower jokes. A comedy with a chamber orchestra very different from the weight of Wagner’s work or, indeed, Strauss’s early work.